Theories of substance abuse

The 17th-century and the moral model of

addictions

The nineteenth century and the first disease

concept

The temperance movement saw drink as an evil; people were seen as victims of alcohol. A similar attitude insisted during the prohibition era in the USA. The first disease concept of addiction considered alcoholism as an illness. Alcoholics were viewed as passively succumbing to the influence of the addictive substance.

The 20th-century and the second

disease concept.

The US government learned that banning alcohol consumption was problematic and governments across the world realised that alcohol could raise high levels of taxation. At this time attitudes towards human behaviour were becoming more liberal. The small minority who consumed alcohol to excess was seen as having a problem, but for the rest of society alcohol consumption once more became an acceptable social habit. The emphasis was on treating addicted individuals.

The 1970s and onwards social learning

theory

With the development of behaviourism, learning theory and a belief that behaviour is shaped by interactions with the environment and other individuals, the belief that excessive behaviour and addictions are illnesses is being challenged. Addictions are seen as learned behaviours. The term " addictive behaviour" has replaced "addictions". Concepts such as addictions, addict, illness and disease are now challenged; the emphasis is now on treatment.

Development of the Disease Model

Problems with the Disease Model. There are some problems with the disease model, the main one being that the nature of the disease has never been identified. What sort of disease is it, and how can a disease make people take drugs? There have been a number of attempts to explain the abuse of specific drugs in terms of a disease process; for example, it has been suggested that alcoholism is a result of a type of food allergy to the grain from which alcohol is manufactured, but such attempts have been limited to a specific drug and have never been particularly convincing.

There has never been a comprehensive disease theory that suggests a mechanism that can account for all types of addictions as a single disease, Perhaps this is not necessary, but considering the similarity of different addictions, it would be scientifically pleasing, and much more useful, if one theory could explain many different addictions. The continued absence of any disease mechanism that can account for the compulsive use of specific drugs or addictive behavior in general makes it increasingly difficult to accept the belief that addiction is a pathological condition.

Development of the Physical Dependence Model

Early biochemical explanations of addiction drew attention to the sickness that develops when a user of opium or morphine tries to stop. These explanations proposed a hypothetical substance called an autotoxin, a metabolite of opium that stayed in the body after the drug was gone. This autotoxin had effects opposite to opium and when left in the body made the person very sick. Only opium or a related drug could antagonize the extremely unpleasant effects of the autotoxin and relieve the sickness. It was believed that the sickness was so unpleasant that the relief provided by opium was responsible for the continuous craving for more opium (Tatum & Severs, 1931).

Later, the existence of the autotoxin was disproved. The sickness that remained after the drug was gone was called a withdrawal symptom or abstinence syndrome, and more accurate explanations were developed to account for it, but avoidance of withdrawal was still regarded as the explanation for opium use and the compulsive craving for the drug. The term physical dependence or physiological dependence was used to describe the state where the discontinuation of a drug would cause withdrawal symptoms.

By itself, the physical dependence model does not explain individual differences as well as the disease model does, but the two models are not incompatible, and often they are combined. For example, there could be a disease that alters the speed of onset with which a person develops physical dependence, or there might be a disease that changes a person's sensitivity to drugs or drug withdrawal. Such a disease would make a person more vulnerable to developing a physical dependence.

One of the strengths of the physical dependence model is that it is more general than the disease model and can apply to any drug that causes dependence. It seems to work well for abuse of the opiates, alcohol, and barbiturates, but it does not offer an explanation for the use of many other drugs like cocaine and cannabis that do not cause obvious withdrawal sickness at abused doses.

There was also a widespread belief that only "depressants" (opiates, alcohol, etc.) would create physical dependence, and only these drugs would cause true dependence (Tatum & Seevers, 193l). Stimulant drugs like cocaine, by definition, were not addicting.

Problems with the Physical Dependence Model. There are two problems

with the physical

dependence model and any disease mechanism that uses its assumptions. To

begin with, it is known that powerful compulsive drug abuse can develop to

substances like cocaine and marijuana that cause only mild (if any) withdrawal,

and second, recent research has shown that even with drugs like heroin that can

cause physical dependence, many people (and laboratory animals) can become

addicts without developing physical dependence. In fact, the definition of

substance dependence in the DSM-IV recognizes that it is possible to be

dependent without being physically dependent, although it suggests that the

presence or absence of physical dependence should be noted in the

diagnosis. Psychological

addiction.

Development of the Positive Reinforcement Model

One assumption that was widely made up until the mid-1950s and held back the development of new ideas and properly controlled scientific research was that addictive behaviour was uniquely human. Attempts to create addictions in other species had generally been unsuccessful. As early as the 1920s it was shown that laboratory animals could be made physically dependent if they were forced to consume a drug like morphine or alcohol, but it could never be shown that they would make themselves physically dependent (then believed to be the defining feature of addiction) if a drug were freely made available to them. Even animals made physically dependent by forced consumption seldom continued to consume a drug when alternatives were made available. The sociologist A. R. Lindesmith, for example, wrote the following in 1937: "Certainly from the point of view of social science it would be ridiculous to include animals and humans together in the concept of addiction" (quoted in Laties, 1986, p. 33).

In the absence of laboratory techniques that could test it, the physical dependence model seemed to account nicely for addiction and was virtually unchallenged until a few simple technological breakthroughs were made in the 1950s. At that time a number of researchers began to show that laboratory animals would learn to perform behaviour that resulted in drug injection. This line of research expanded quickly when the technology was developed that allowed drug infusions to be delivered intravenously to freely moving animals by means of a permanently implanted catheter. With this one development, our whole view of drug self-administration changed.

Because of the pervasive influence of the physical dependence model, in these early studies it was assumed that physical dependence was essential for drug self-administration. Thus rats and monkeys were first made physically dependent on morphine by repeated injections. Then they were placed in an operant chamber and were given the opportunity to press a lever that caused a delivery of morphine through a catheter. The animals quickly learned to respond. It became obvious that the drug infusion was acting like a more traditional positive reinforcer such as food or water (Thompson & Schuster, 1964).

This and many other studies have clearly demonstrated that many of the assumptions of both the disease model and the physical dependence model are not correct. They have shown that while physical dependence can be an important factor controlling the intake of some drugs, it is not necessary for drug self-administration and cannot serve as the sole explanation for drug taking. These studies also showed that drug self-administration behaviour obeys the same laws that govern the normal behaviour of all animals in similar situations. There is no advantage to considering drug abuse as a disease: it can be understood in terms of operant conditioning theory.

The model of drug taking that has developed as a result of these studies is called the positive reinforcement model. This model assumes that drugs are self-administered because they act as positive reinforcers and that the principles that govern behaviour controlled by other positive reinforcers apply to drug self-administration.

The Positive Reinforcement Paradox

While it seems clear that drugs act as positive reinforcers, it does not seem obvious how this model can account for some aspects of addictive behavior. The consequences of using some drugs can be painful and unhealthy and ought to be punishing enough to make an organism stop using them. For example, when cocaine and amphetamine are made freely available to a monkey for a period of time, very often it will refuse to eat or sleep for extended periods, the drug will cause it to mutilate parts of its body, and ultimately the monkey will die of an overdose or bleed to death from its own self-inflicted wounds, not unlike the economically and physically destructive human behavior motivated by cocaine in some humans. It may seem contradictory that behavior inspired by positive reinforcement should continue on in spite of such punishing consequences. Addicts themselves often acknowledge that continued drug use creates an aversive state they generally would like to avoid or terminate (anonymous, personal communication, November 21, 1997). For this reason drug users often seek treatment for their addiction. How can an event like the administration of a drug be both positively reinforcing enough to make people continue to use it? And at the same time be aversive enough to motivate people to stop. As anonymous of Bangor ME asks. If addictive drug use is positively reinforcing, then why would a user ever want to stop(anonymous, personal communication, November 21, 1997) ? Such a paradox is not unique to drugs. There are many examples where consumption of more traditional reinforcers such as food is destructive and causes pain. People often overeat, become obese, and experience physical discomfort, health risks, and social censure. Sexual activity also acts as a reinforcing stimulus. It has positive reinforcing effects but can also have the potential to cause unpleasant and undesirable consequences such as sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancy. In fact, most positive reinforcers, including drugs, can have negative destructive effects that can motivate people to seek treatment to help them stop.

One of the reasons that positive reinforcing effects continue to control behavior is that they are immediately experienced after behavior, whereas the punishing and painful effects are often delayed. One well-understood principle of operant conditioning is that if a consequence is delayed, its ability to control behavior is diminished. Thus if a drink of alcohol causes pleasure within minutes and a hangover a number of hours later, it is the pleasure rather than the hangover that will be more likely to determine whether the person will drink again. When punishing consequences occur infrequently and after a considerable delay no matter how severe they might be, they are less likely to exert as much control over behavior as immediate gratification.

Classical conditioning

External cues (e.g. pub) are associated with drink, for example. Internal cues (e.g. anxiety) are associated with smoking, for example. In the case of smoking and anxiety, a withdrawal effect is anxiety, which in turn produces anxiety and a strong urge to smoke; a vicious circle.

Other factors

Modelling through copying parents.

Cognitive factors such as self-image, solving a personal problem or as a coping mechanism.

Sociocultural Effects

Sociocultural factors, triggered by substance use, can also contribute to progression in use. An individual who initiates use, for example, may begin to participate in a subgroup that encourages use, such as the patrons of crack houses, groups of heroin users, members of substance-using motorcycle gangs, adolescent peer groups, cocktail party groups, after-work beer groups, and groupies who follow certain rock bands. (In some cases, too, such groups and subcultures may provide the impetus for the initiation of use as well.) Such social and cultural environments encourage, reinforce, maintain, and increase substance use and abuse--all of which can develop after the initiation of use outside the group. Conversely, the lack of rewarding, substance-free alternative groups and activities may render individuals more vulnerable to the appeals of substance- using groups and subcultures.

STAGES IN THE INITIATION OF USE

Do individuals first use one substance (e.g., alcohol or tobacco) and only later use another (e.g., cocaine or heroin)? Are stages in the first use of different substances similar across cultures? Does the use of one substance (e.g., marijuana) directly increase the likelihood of later use of another substance (e.g., heroin)? Or is progression in use caused more by other mediating factors, such as multiple behavior problems? If so, might these other problems contribute to later use of certain substances even in the absence of the use of other substances earlier on?

The basic question about whether there are stages in the initiation of the use of different substances has been studied in the United States (9,11,12,21,27) and in Israel and France (1). While study results vary somewhat, the sequence most often reported is that alcohol and cigarette use come first, followed by marijuana use and then by the use of other illicit substances. Some variations in this sequence have been found for individuals of different sexes, racial and ethnic groups, and cultures. The idea that the use of some substances increases the likelihood of the use of other substances has led to several hypotheses.

The Stepping Stone Hypothesis

In its strongest form, the so-called "stepping stone" hypothesis asserted that the use of marijuana often or almost always led to violent crime and to the use of other illicit substances (28). This hypothesis has never been proved. An even earlier version of the stepping stone hypothesis goes back to the beginning of the 20th century, when the presumed progression from tobacco to alcohol to morphine use was presented as an argument for prohibiting both alcohol and tobacco. One observer commented that there was no strong evidence that the use of these substances causes progression from one to another; rather, some individuals are more prone to the use of multiple substances. Also, the criminalization of marijuana may have caused some marijuana users to move on to other illicit substances through contact with the subculture of illicit users (14).

The Gateway Hypothesis

More recently, a more moderate hypothesis, the gateway hypothesis, has been put forward. It asserts that use of certain substances increases somewhat the chances of progression to the use of other substances. For example, in one longitudinal study, men who had used both alcohol and cigarettes by age 15 had a 52 percent greater chance of using marijuana, compared to men who had never used alcohol or cigarettes by age 25 (26). For women, the increased chance of marijuana use among alcohol and cigarette users was 46 percent. Similarly, for the next stage, men who had used marijuana by age 15 had a 68 percent greater chance of initiating the use of other illicit substances, compared with those who had never used marijuana. For women, the increased probability was 53 percent. Interestingly, Lynskey, Fergusson, and Horwood (1998) concluded from analysis of their large New Zealand cohort study that correlations between tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs use during adolescence largely arise from common risk factors and/or sources of vulnerability that precede the onset of substance use. This data runs counter to the gateway theory of causal linkages between substances: i.e. that use of one substance leads to use of another.

Non-use of a Substance at an Earlier Stage

Because of variations among communities and cultures, the search for a universally applicable sequence in the initiation of the use of different substances may be less fruitful than the study of why there may be somewhat different sequences, depending on factors such as availability and social norms. The relative ease of availability of some substances (e.g., cigarettes, beer, wine) may well account for their frequent appearance at an early stage in the sequence of use. However, this may vary among cultures. In France, for example, wine is widely available and used both at an early age and at an early stage in the sequence. In other cultures, where wine is less available but inhalants are widely available and inexpensive, inhalants are used at an early age and early in the sequence. Use at a young age may be a marker, at least in some cultures, for other risk factors, such as parental substance abuse and other family problems, which can contribute to later substance abuse problems, independently of early and frequent use. For example, one study found that, irrespective of the age of onset of use, individuals who exhibited numerous behavioral problems in their youth moved on to problem substance use, no matter how early or late in their youth they began to use substances (20).

STAGES IN THE CYCLE OF USE, ABUSE, AND ADDICTION

One approach to the study of stages in substance use focuses not just on the initiation of use; but also on the continuation of use, maintenance and progression of use within a class of substances; progression across classes; and regression, cessation, and relapse cycles in use and abuse (2).

The predictors of smoking initiation and maintenance

Parental smoking. The children are twice as likely to smoke

If parents are strongly against smoking then the children are seven times less likely to smoke

Those labelled by themselves or others as being problem prone, low in self-esteem, poor at school, not sporting, high in risk taking behaviour (drink alcohol, take drugs) are more likely to smoke.

But other research has found high rates of smoking amongst children who are seen as leaders of academic and social activities, who have high self-esteem, and are popular with peers.

Cancer research campaign (1991) smoking is lower in children who attend schools that have a total ban on smoking.

Initiation is clearly a key first step in the progression to more serious levels of use. Because substance use is often initiated during adolescence, most substance use research has focused on initiation of use among adolescents. However, most individuals who initiate substance use do not progress to harmful use. Also, the factors associated with such progression may often differ from the factors associated with initiation. Thus, the focus on the initiation of use during adolescence is not sufficient for an understanding of the progression from use to abuse and addiction.

Smoking in children. If you have tried to smoke why did you?

Children and adolescents are more

likely to smoke if their parents and friends smoke (Hansen et al, 1987). The first cigarette is often smoked in the

company of peers, who give their encouragement (Leventhal et al, 1985). This is in line with theories of modelling

and peer pressure. Smoking is

associated, amongst adolescents, with being attractive or being tough (Barton

et al, 1982).

Doll & Peto (1981) – Childhood smokers have an increased risk of lung cancer in adulthood.

Smoking in 11-15 year olds has fallen between 1982-1990 with boys dropping from 55% to 44% and girls dropping from 51% to 42%. 50% of all children have tried at least one cigarette.

Continuation of Use. If you smoke why do you continue to do so? If you have smoked why did you stop?

Individuals who smoke their fourth cigarette are likely to become regular (Leventhal & Cleary, 1980). The habit takes a year or more to develop.

After trying a substance for the first time, one person may say, "I won't be trying that again," while another may say, "That's for me." Although only limited research has been conducted on risk and protective factors associated with the transition from experimentation to continued use, the continuation of use can apparently be influenced by the pharmacology of the substance (e.g., whether it produces desired or pleasant experiences), the biology of the individual (e.g., whether specific individuals have genetic or acquired biological predispositions or intolerances to the use of specific substances), the availability and marketing of the substance (e.g., whether a substance is widely available, used, and accepted for use), other characteristics of the individual (e.g., at what developmental stage one is, and whether one has mental or emotional problems, which may be ameliorated at least temporarily by substances), and community contexts (e.g., substance-using subcultures or settings that strongly encourage and reinforce a continued use of substances).

STAGES IN PROBLEM BEHAVIORS

Does substance use itself contribute to conduct disorders, delinquency, and other problem behaviors? Do these behaviors then, in turn, contribute to the progression to more use and to abuse and addiction?

Adolescents who use substances, especially those that are illegal, are more likely than nonusers to exhibit various problem behaviors, including: early sexual experimentation, delinquent activities, eating problems, and psychological or psychiatric problems, including suicide and suicidal thoughts (10). Less is known, however, about the sequencing of these behaviors. The interrelations among the factors is likely to vary widely among individuals, but some sequences may predominate. Several such sequences have been proposed. One suggested developmental sequence, for example, includes six stages: oppositional (characterized by disobedience at home); offensive (including disobedience in school, fighting, lying); aggressive (physical attacks on others, theft at home); minor delinquency (shoplifting and status offenses, such as alcohol use, truancy, running away); major delinquency (break-in and entry, car theft, substance abuse, robbery, drug dealing); and violence (assault, rape, homicide) (15).

One of the few studies of problem behavior sequences looked at the order of initiation of four different substances, delinquency, and sexual activity, among a sample of black adolescents (3). For males, it found involvement proceeded generally from beer use to cigarette use, then to delinquency, sexual activity, marijuana use, and the use of hard liquor. For females, the progression was generally from cigarette use, to delinquency, beer use, sexual activity, marijuana, and hard liquor. For both sexes, delinquency and youthful sexual activity tended to precede the use of marijuana and hard liquor.

Expectations and Effects of Use

The expectations and effects of use can also reinforce use and influence progression from use to abuse and addiction. Research reviews have discussed some examples of the expectations and effects of using illicit substances that can reinforce their use and may increase the likelihood of progression to abuse and addiction (13,25). These purposes include:

o The reduction of negative feelings, including the use of stimulants to alleviate depression and weakness; psychedelics to combat boredom and disillusionment; alcohol to assuage feelings of guilt, loneliness, and anxiety; and tranquilizers, amphetamines, and sedatives to reduce painful feelings.

o The reduction of self-rejection. Some researchers have found an association between substance use and indices of insecurity, dis-satisfaction with self, desire to change oneself, defensiveness, low self-esteem, and low self- confidence.

o The increase in potency. Increases in physical and sexual potency, daring, and toughness can be achieved by using specific substances in certain situations. This can be especially appealing to youth, who may be wrestling with feelings of powerlessness, dissatisfaction, and frustration.

o The expression of anger. Substances can heighten expressions of anger (e.g., in opposition to mainstream norms) or can medicate away anger and rage. Narcotics and hypnotics may help reduce rage, shame, jealousy, and impulses toward extreme aggressiveness.

o The achievement of peer acceptance. Peers often play the largest role in endorsing and encouraging substance use, and in supplying substances. The initiation, continuation, and progression of use can be important ways for individuals to gain acceptance into peer groups. This can be true in school (e.g., in a fraternity), at work (e.g., in a sales force that demands that one be able to "hold one's liquor"), in substance-using gangs, and among certain groups of artists (e.g., some contemporary painters and musicians).

o The seeking of euphoria. Many substance users, especially addicts, report favorably on drug-induced euphoria. Indeed, the prospect of euphoria may be the initial attraction of the substance. It can also encourage continued use, even to the point of addiction and negative consequences.

o The coping with problems. For some users, substances temporarily alleviate problems they have been unable to resolve in other ways. While the problems may be causing emotional pain, the use of substances, especially for the young, can inhibit the development of other problem-solving skills and may alleviate symptoms only in the short-run, since the underlying causes of the problems are likely to remain unresolved.

o The reduction of overwhelming trauma. Post-traumatic stress (e.g., after a war, or after physical or sexual abuse) can result in the use of addictive substances, since use may temporarily reduce fears, flashbacks, and other negative feelings.

o The suppression of appetite or hunger. Another function of using some psychoactive substances is appetite suppression. An extensive literature exists on the use of nicotine, from cigarette smoking, to control appetite and weight. This phenomenon often manifests itself in the negative: for example, current smokers (especially women) are reluctant to stop smoking for fear they will gain weight (4).

o The seeking of stimulus. Individuals who seek higher levels of external stimulation can also turn to substances, for a high, for hallucinations, for unpredictable effects.

o The regulation of affective and behavioral impairments. Those with mood disorders, such as depression, and behavioral impairments may find that some substances alter moods and allow them to modify behaviors.

SUMMARY

Substance use, including the progression to heavier and more harmful use, is a precondition and contributor to abuse and addiction. Researchers have focused on stages in the progression of substance use in several ways. They have studied stages in the initiation of the use of different substances, finding a sequence that moves from the use of cigarettes and wine or beer, to the use of marijuana, then hard liquor, and finally other illicit substances. Because many individuals who use substances do not go on to substance abuse, and because use at one level does not guarantee use at a higher level, these stages are descriptive but not predictive.

In addition to the biologically and pharmacologically reinforcing properties of addictive substances that can lead to tolerance and dependence, key aspects of substance use that contribute to abuse and addiction include age of first use, the frequency, quantity, and type of substance used, and the techniques and expectations and effects of use. _

Theories

The biobehavioural model (Ovide and Cynthia Pomerlean 1989)

Smokers depend on nicotine to regulate their cognitive and emotional states. They need nicotine to cope.

However, a full explanation would involve the interplay of biological, psychological and social factors (Ashton and Stepney, 1982).

Griffiths 1995.

Addictive behaviours have six components:

- Salience – how important the behaviour seems

- Euphoria

- Tolerance

- Withdrawal symptoms

- Conflict – with people around them

- Relapse – a high chance of relapse

Addicts need to reinvent themselves. They see themselves as a sinner, a drunk, or as hedonistic. They feel the need to become moral. This is in accordance with the moral model, but reinvention would not necessarily entail a moral adjustment.

Society

Society places different values on drugs. The ones that receive most attention may not necessarily be the most dangerous. For example, it is considered politically correct to expend a good deal of energy attacking ecstasy. Ecstasy can kill, but has killed far fewer people than those who are killed on the roads. A political party who attacked the individual right to run a private car at an affordable cost would be committing political suicide, whereas an attack on ecstasy would contribute to their success in the next elections. In October 2001 the British government, on police advice, reduced the status of cannabis from a class B classification to the less serious class C; However, ignoring police advice ecstasy remained classified as a class B drug.

Silvan Tomkins (1968)

Smokers smoke in order to achieve a positive affect such as stimulation, relaxation, pleasure; also the reduction of negative affect such as the relief of anxiety or tension.

So smoking is seen as a habitual or automatic behaviour and psychological dependence is seen as the regulation of positive and negative emotional states.

An experiment

To demonstrate positive affect, smokers who had access only to cigarettes that had been dipped in vinegar, smoked less than controls.

To demonstrate negative affect, smokers smoked more cigarettes after a fear arousing film. Wills (1986) has also reported that the more stressed people are the more likely they are to smoke.

Nicotine

Nicotine is absorbed into the mouth and nose; it is quickly transported to the brain via the blood. Within seconds nicotine triggers the release of chemicals that activate the central and sympathetic nervous systems. Nicotine arouses the body, increases alertness, increases heart rate, and increases blood pressure. Nicotine accumulates rapidly but is half strength 20 to 60 minutes after a cigarette.

Nicotine regulation model

Smokers smoked more low nicotine cigarettes during a week when all they had was low nicotine cigarettes; compared to fewer high nicotine cigarettes in another week when only high nicotine cigarettes were available. Many people crave cigarettes long after the nicotine has gone. This could be owing to the direct reinforcing effects of nicotine. Those who smoke few cigarettes probably do so because of reinforcing effects.

Alcohol

25% of men and women did not drink and gave reasons such as religion or not liking the taste.

Tension reduction hypothesis. Is probably the expected effects rather than the actual effects that cause people to drink in order to reduce tension.

A smaller amount of alcohol reduces tension, so people continue to drink a large amount of alcohol in the belief that it will reduce tension, when in fact it does not.

Parental drinking is predictive of alcohol consumption in their children. This is probably through "social hereditary factors" rather than genetic (predisposition). But twin and adoption studies have shown a modest link between genes and alcohol consumption. Other factors would be the attitudes of the peer group, sensation seeking, aggressiveness, and a history of getting into trouble.

Neurotransmitters

Without going into a full biology lesson, a neurotransmitter is a chemical which moves in the gaps between nerve cells to transmit messages. Ifthe chemical is blocked or replaced, for example, then the message changes and there is an effect on the physiological systems, and also on cognition, mood and behaviour. The neurotransmitter that is most commonly implicated in all this is dopamine, but a range of other chemicals has also been found to have an effect (Potenza, 2001).

The difficulty with looking

at which neurotransmitter produces which reward is that — to state the blindingly

obvious — the brain is remarkably

complex, and the effects of even one drug can be very diverse. Ashton and Golding

(1989) suggest that nicotine can simultaneously affect a number of systems

including learning and memory, the control of pain, and the relief of anxiety.

In fact, it is generally believed that smoking nicotine can increase arousal

and reduce stress —

two responses

which ought to be incompatible (Parrott, 1998). This means that it is difficult

to pin down a single response that follows smoking a cigarette. A deeper

problem with the neurochemical explanations is that they can neglect the social context of the behaviours. The

pleasures and escapes associated with taking a drug are highly varied and

depend on the person, the dose, the situation and the wider social context in

which they live (Orford, 2001).

Genetics

Until relatively recently

the main way of investigating genetic factors

in human behaviour was to study family relationships. More recently it has been

possible to carry out genetic analysis and look for differences in the genetic

structure of people with and without addictive behaviours. The two methods tend

to point to different answers. The family studies emphasise the role of environmental factors in the development

of addictive behaviours. A study of over 300 monozygotic twins (identical) and

just under 200 same-sex dizygotic twins (fraternal) estimated the contribution

of genetic factors and environmental factors to substance use in adolescence.

It concluded that the major influences on the decision to use substances were

environmental rather than genetic (Han et

al., 1999). Some family studies, however, suggest there is a link between

addictive behaviour and personality traits. For example, a study of over 300

monozygotic twins and over 300 dizygotic twins looked at the relationship

between alcohol use and personality. The study suggests that there is a

connection between genetics and anti-social personality characteristics

(including attention-seeking, not following social norms, and violence), and

between these personality characteristics and alcoholism (Jang et al., 2000).

Studies that analyse the

genetic structure of individuals tend to emphasis the role of genetics (rather than the environment)

in addictive behaviours. Some genes have attracted particular attention and

have been shown to appear more frequently in people with addictive behaviours

than in people without. The problem is that these genes do not occur in all

people with the addictive behaviour and they do appear in some people without

it. For example, a gene referred to as DRD2 (no, he didn’t appear in Star Wars)

has been found in 42 per cent of people with alcoholism. It has also been found

in 45 per cent of people with Tourettes syndrome and 55 per cent of people with

autism. It has also been found in 25 per cent of the general population. This

means that DRD2 appears more frequently in people with these behavioural

syndromes, but it cannot be the sole explanation for the behaviour (Comings,

1998).

Availability

There are a number of

environmental factors that affect the incidence of addictive behaviours in a

society. Two factors which affect the level of alcoholism are the availability of alcohol, and the average consumption of alcohol by the

general population. Comparison studies have found near perfect correlations

between the number of deaths through liver cirrhosis (generally attributed to

alcohol abuse) and the average consumption of alcohol in different countries

(for a discussion see Orford, 1985). The availability factor also affects the

consumption of cigarettes, as shown in the study below.

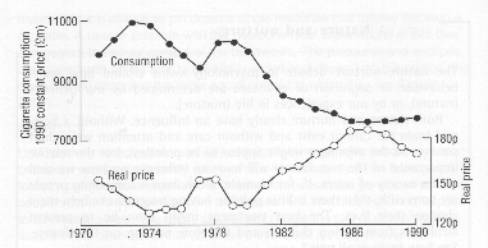

Fig 1

If we

examine the pattern of cigarette consumption compared with the retail price of

cigarettes in the UK we can observe a remarkable relationship. Figure 1

shows how the curve for consumption is the mirror

image of the curve for retail price (Townsend, 1993). Since 1970 any increase

in price has brought about a decrease in smoking. At the time of the study

there was a slight decrease in the price of cigarettes (figures adjusted to

take account of inflation) and a corresponding rise in smoking. This rise in

smoking was particularly noticeable in young people and, according to Townsend

(1993), regular smoking by 15-year-old boys increased from 20 per cent to 25

per cent and by 16—19-year-old girls from 28 per cent to 32 per cent. This

connection between price and consumption suggests an obvious policy for

governments who want to reduce smoking.

shows how the curve for consumption is the mirror

image of the curve for retail price (Townsend, 1993). Since 1970 any increase

in price has brought about a decrease in smoking. At the time of the study

there was a slight decrease in the price of cigarettes (figures adjusted to

take account of inflation) and a corresponding rise in smoking. This rise in

smoking was particularly noticeable in young people and, according to Townsend

(1993), regular smoking by 15-year-old boys increased from 20 per cent to 25

per cent and by 16—19-year-old girls from 28 per cent to 32 per cent. This

connection between price and consumption suggests an obvious policy for

governments who want to reduce smoking.

The relationship between

affluence and drug use is apparent from drug use figures for 2001-02. In England and Wales the use of Ecstasy has

fallen by 20%, but affluent urban dwellers have increased their drug use. The use of any illicit drugs in such areas

is now put at 21.8% (see chart) (Times 5-12-03).

Social cues: tobacco advertising

In their response to the Health of the Nation strategy (D0H,

1992), the British Psychological Society (1993) called for a ban on the

advertising of all tobacco products. This call was backed up by the

government’s own research (D0H,1993) which suggested a relationship between advertising and sales.

Also, in four countries that have banned tobacco advertising (New Zealand,

Canada, Finland and Norway) there has been a significant drop in consumption.

Public policy, however, is

not always driven by research findings, and the powerful commercial lobby for

tobacco has considerable influence. In her reply to the British Psychological

Society, the Secretary of State for Health (at that time Virginia Bottomley)

rejected an advertising ban, saying that the evidence was unclear on this issue

and that efforts should be concentrated elsewhere. This debate highlights how

issues of addictive behaviours cannot be discussed just within the context of

health. There are a range of political, economic, social and moral contexts to

consider as well. At the time of writing, both the British government and the

European Community have now made commitments to ban tobacco advertising in the

near future.

Recommended Reading

Banyard. P., Psychology in Practice – Health, Hodder & Stoughton, 2002, 0-340-84496-5

Ogden. J., Health Psychology, Open University Press, 1996.

Sarafino. E.P., Health Psychology, Wiley, 1994.