Preventing and Quitting Substance abuse.

Health Promotions

Material adapted from Jane Ogden's

excellent book, 'Health Psychology', Open University Press, 1996, Chapter 5, in

the hope that you will buy it, either for yourself or as a class set.

Arm patch monitors alcohol tolerance

Patterns and predictions of smoking cessation among British Women (Graham and Der, 1999)

Guardian article on idea for persuading teenagers not to smoke

Battle begins in junkies' very personal war zone

TESTING A THEORY - STAGES OF SMOKING CESSATION

Smoking is highly resistant

to change. Once established it is maintained by addictive and conditioning processes

as well as social factors. It is also an effective method of moderating stress

(Shiffman 1986). This combination of factors suggests that interventions to

help smokers cease smoking have to address a number of issues, and that more

complex interventions may be more effective than simple exhortations to quit,

even when these are combined with some minimal support.

The American Lung Association

programme, for example, has a programme involving a specific quit date,

interruption of conditioned responses supporting smoking, identification and

preparation of plans for coping with temptations after cessation, teaching

relapse prevention skills, and follow-up contact and support. This programme,

and its variants, has achieved long-term abstinence rates of between 35 and 29

per cent (Lando et at. 1989;

Rosenbaum and O’Shea 1992).

A study to examine the stages of change in

predicting smoking cessation

(DiClemente et al1991)

DiClemente and Prochaska (1982) developed their transtheoretical model of change to examine the stages of change in addictive behaviours. This study examined the validity of the stages of change model and assessed the relationship between stage of change and smoking cessation.

The stages of change model describes the following stages:

* Precontemplation: not seriously considering quitting in the next 6 months.

* Contemplation: considering quitting in the next 6 months.

* Action: making behavioural changes.

* Maintenance: maintaining these changes.

Individuals move backwards and forwards across the stages. In this study, the authors categorized those in the contemplation stage as either contemplators (not considering quitting in the next 30 days) and those in the preparation stage (planning to quit in the next 30 days).

Subjects 1466 subjects were recruited for a minimum intervention smoking cessation programme from Texas and Rhode Island. The majority of the subjects were white, female, started smoking at about 16 and smoked on average 29 cigarettes a day.

Design The subjects completed a set of measures at baseline and were followed up at 1 and 6 months.

Measures The subjects completed the following set of measures:

* Smoking abstinence self-efficacy (DiClemente et al. 1985), which measures a smoker's confidence that they will not smoke in 20 challenging situations.

* Perceived stress scale (Cohen et al. 1985), which measures how much perceived stress an individual has experienced in the past month.

* Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire, which measures physical tolerance to nicotine.

* Smoking decisional balance scale (Velicer et al. 1985), which measures the perceived pros and cons of smoking.

* Smoking processes of change scale (DiClemente and Prochaska 1985), which measures an individual's stage of change. According to this scale, the subjects were defined as precontemplators (n = 166), contemplators (n = 794) or as being in the preparation stage (n = 506).

* Demographic data, including age, gender, education and smoking history.

At baseline the results showed that those in the preparation stage smoked less, were less addicted, had higher self-efficacy, rated the pros of smoking as less and the costs of smoking as more, and had attempted to quit more often than the other two groups. At both 1 and 6 months, the subjects in the preparation stage had attempted to quit more often and were more likely not to be smoking.

With regard to motivation intrinsic motivation was far better than extrinsic motivation in bringing about positive changes in behaviour (DiClemente 1999). It is therefore important to change external reasons for quitting into internal reasons.

Interventions to promote cessation

Interventions to promote cessation can be described as:

- (1) clinical interventions, which are aimed at the individual,

- (2) self-help movements

- (3) public health interventions, which are aimed at populations.

Clinical interventions: promoting

individual change

Disease perspectives on cessation

Nicotine fading procedures encourage smokers gradually to switch to brands of low nicotine cigarettes and gradually to smoke fewer cigarettes. It is believed that when the smoker is ready to quit completely, their addiction to nicotine will be small enough to minimize any withdrawal symptoms. Although there is no evidence to support the effectiveness of nicotine fading on its own, it has been shown to be useful alongside other methods such as relapse prevention (e.g. Brown et al. 1984). But other evidence shows that people compensate by smoking more low-nicotine cigarettes.

Nicotine replacement. For example, nicotine chewing gum. The chewing gum has been shown to be a useful addition to other behavioural methods, particularly in preventing short-term relapse (Killen et al. 1990). However, it tastes unpleasant and takes time to be absorbed into the bloodstream. More recently, nicotine patches have become available and only need to be applied once a day in order to provide a steady supply of nicotine into the bloodstream. They do not need to be tasted, although it could be argued that chewing gum satisfies the oral component of smoking. However, whether nicotine replacement procedures are actually compensating for a physiological addiction or whether they are offering a placebo effect via expecting not to need cigarettes is unclear.

Meta-analysis suggested that nicotine gum can increase the effectiveness of cessation interventions (Lam et al. 1987). However, a considerable part of its effectiveness seems to lie in its placebo value (Lichtenstein and Glasgow 1992). Double-blind studies where the gum has been used in isolation have provided only mixed evidence of its effectiveness. Only when the gum has been used in combination with psychological support has its use been consistently and substantially effective (Lam et at. 1987). However, some failures to find this additive effect have been reported (e.g. Hall et al. 1987). Why this should occur is unclear. One explanation for these negative findings, however, may lie in the attributions smokers make for the success of their efforts in cessation. If success is attributed to the use of nicotine gum and not to personal coping resources, this may set up expectations of relapse when the gum is no longer used — an expectation, which can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The equivocal success of nicotine may, at least in part, reflect the characteristics of the gum and its inappropriate use. The gum intentionally tastes unpleasant and its absorption through the mucosa can be suppressed by drinking coffee or soft drinks. Accordingly, many smokers do not use the gum sufficiently to maintain therapeutic blood levels. More acceptable, and consistent, may be the use of nicotine patches which absorb nicotine through the skin and maintain more consistent levels of plasma nicotine levels through the day. These have been shown to be more effective than a placebo (Richmond et al. 1994), and may enhance the impact of any behavioural intervention. Richmond et at. (1994), for example, compared the effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioural intervention in combination with either active or placebo nicotine patches. Participants using the active nicotine patch were most likely to be abstinent at the three (48 versus 21 percent) and six-month (33 versus 14 per cent) follow-up assessments. Six-month continuous abstinence rates were also higher among the active nicotine group (25 per cent) than the control group (12 per cent).

Smokers are not a homogenous group. Some smokers may smoke

predominantly out of habit; some due to an addiction to nicotine (Fagerstrom

1982). Accordingly, the same therapeutic approach may not be optimal for both

groups. Indeed, there is evidence that cognitive-behavioural approaches may be

best for those who smoke predominantly out of habit, while nicotine

replacements in combination with some form of psychological intervention may

prove optimal for those with high levels of nicotine dependency. Evidence in

support of this hypothesis was provided by Hall et at. (1985), who assigned high and low nicotine-dependent smokers

to either an intensive behavioural intervention, nicotine gum, or a combination

of both approaches. At the one-year follow-up, 50 per cent of high

nicotine-dependent smokers in the combined intervention were not smoking. This

compared with abstinence rates of 28 per cent among the equivalent group in the

nicotine gum condition, and 11 per cent of those who participated in

behavioural intervention. In contrast, low dependent smokers gained most from

the behavioural intervention. Among this group, abstinence rates at one year

were 47 per cent, in comparison to rates of 42 and 38 per cent in the nicotine

gum and combined interventions.

Even where individuals have failed to quit on one attempt, it may not be unreasonable to attempt further cessation fairly quickly if the individual remains motivated to change. Gourlay et al. (1995), for example, randomly allocated 629 smokers who had previously failed to quit smoking while using transdermal patches to either a placebo control condition or a further intervention comprising transdermal nicotine patches, brief behavioural counselling (five to 10 minutes) and a booklet containing advice on smoking cessation and instructions for the use of patches. While quit rates were, perhaps unsurprisingly, relatively low there was still evidence of some benefit from the combined intervention, with six-month abstinence rates of 6.4 per cent of those receiving the active intervention and 3.8 per cent in the placebo condition.

Social learning perspectives on cessation

1 Aversion therapies aim to punish smoking rather than reward it. Early methodologies used crude techniques such as electric shocks, whereby each time an individual puffed on a cigarette or drank some alcohol they received a mild electric shock. However, this approach was found to be ineffective for smoking and drinking (e.g. Wilson 1978), the main reason being that it is difficult to transfer behaviours, which have been learnt in the laboratory to the real world.

Imaginal aversion techniques have been used among smokers and encourage them to imagine the negative consequences of smoking, such as being sick (rather than actually experiencing them). However, imaginal techniques seem to add nothing to other behavioural treatments (Lichtenstein and Brown 1983).

Rapid smoking is a more successful form of aversion therapy (Danaher 1977) and aims to make the actual process of smoking unpleasant. Smokers are required to sit in a closed room and take a puff every 6 seconds until it becomes so unpleasant they can't smoke anymore. Although there is some evidence to support rapid smoking as a smoking cessation technique, it has obvious side-effects, including increased blood carbon monoxide levels and heart rates.

Other aversion therapies include focused smoking, which involves smokers concentrating on all the negative experiences of smoking, and smoke holding, which involves smokers holding smoke in their mouths for a period of time and again thinking about the unpleasant sensations. Smoke holding has been shown to be more successful at promoting cessation than focused smoking and it doesn't have the side-effects of rapid smoking (Walker and Franzini 1985).

Contingency contracting. Schwartz (1987) analysed a series of contingency contracting studies for smoking cessation that took place between 1967 and 1985 and concluded that this procedure seems to be successful in promoting initial cessation, but once the contract is finished, or the money returned, relapse is common.

Cue exposure procedures focus on the environmental factors that have become associated with smoking and drinking. For example, if an individual always smokes when they drink alcohol, alcohol will become a strong external cue to smoke and vice versa. Cue exposure techniques gradually expose the individual to different cues and encourage them to develop coping strategies to deal with them. This procedure aims to extinguish the response to the cues over time and is opposite to cue avoidance procedures, which encourage individuals not to go to the places where they may feel the urge to smoke.

Self-management procedures use a variety of behavioural techniques to promote smoking and drinking cessation in individuals and may be carried out under professional guidance. Such procedures involve self monitoring (keeping a record of own smoking/drinking behaviour), becoming aware of the causes of smoking/drinking (What makes me smoke? Where do I smoke? Where do I drink?), and becoming aware of the consequences of smoking /drinking (Does it make me feel better? What do I expect from smoking/drinking?). However, used on their own self-management techniques do not appear to be any more successful than other interventions (Hall et al. 1990).

Multi-perspective cessation clinics represent an integration of the above clinical approaches to smoking and drinking cessation and use a combination of aversion therapies, contingency contracting, cue exposure and self-management. Lando (1977) developed an integrated model of smoking cessation, which has served as a model for subsequent clinics. His approach included the following procedures:

- * six sessions of rapid smoking for 25 minutes for 1 week;

- * a doubling of the daily smoking rate outside the clinic for 1 week;

- * the onset of smoking cessation;

- * identification of the problems encountered when attempting to stop smoking;

- * development of ways to deal with these problems;

- * self-reward contracts for cessation success (e.g. buying something new);

- * self-punishment contracts for smoking (e.g. give money to a friend/ therapist).

Lando's model has been evaluated and research suggests abstinence rates of 76 per cent at 6 months (Lando 1977) and 46 per cent at 12 months (Lando and McGovern 1982), the latter being higher than the control group's abstinence rates. Killen et al. (1984) developed Lando's approach but used smoke holding rather than rapid smoking, and introduced nicotine chewing gum into the programme. Their results showed similar high abstinence rates to the study by Lando.

Self-help movements

Although clinical and public health interventions have proliferated over the last few decades, up to 90 per cent of ex-smokers report having stopped without any formal help (Fiore et al. 1990). Lichtenstein and Glasgow (1992) reviewed the literature on self-help quitting and reported that success rates tend to be about 10-20 per cent at 1-year follow-up and 3-5 per cent for continued cessation. The literature suggests that lighter smokers are more likely to be successful at self quitting than heavy smokers and that minimal interventions such as follow-up telephone calls can improve the rate of success. However, although many ex-smokers report that 'I did it on my own', it is important not to discount their exposure to the multitude of health education messages received via television, radio or leaflets.

Public health

interventions: promoting cessation among populations

1 Doctor's advice. In a classic study carried out in five general practices in London (Russell et al. 1979, see Key Study 4 p43 in Harari and Legge, 2001), smokers visiting their GP over a 4-week period were allocated to one of four groups:

- (1) follow-up only,

- (2) questionnaire about their smoking behaviour and follow-up,

- (3) doctor's advice to stop smoking, questionnaire about their smoking behaviour and follow-up,

- (4) doctor's advice to stop smoking, leaflet giving tips on how to stop and follow-up.

All subjects were followed up at 1 and 12 months.

Results at 12 months

|

Group |

% still abstinent |

|

1 |

0.3 |

|

2 |

1.6 |

|

3 |

3.3 |

|

4 |

5.1 |

Research suggests that the effectiveness of doctor's advice may be increased if they receive training in patient-centred counselling techniques (Wilson et al. 1988). See doctor - patient relationships.

Worksite interventions. Research into the effectiveness of no-smoking policies has produced conflicting results, with some studies reporting an overall reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked for up to 12 months (e.g. Biener et al. 1989) and others suggesting that smoking outside work hours compensates for any reduced smoking in the workplace (e.g. Gomel et al. 1993). In two Australian studies, public service workers were surveyed about their attitudes to smoking bans in 44 government office buildings immediately after the ban and 6 months later. The results suggested that although immediately after the ban many smokers felt inconvenienced, these attitudes improved at 6 months with both smokers and non-smokers recognizing the benefits of the ban. However, only 2 per cent stopped smoking during this period.

A pilot study to examine the effects of a workplace ban on smoking on

craving, stress and other behaviours (Gomel et al. 1993)

The ban was introduced on 1 August 1989 at the New South Wales Ambulance Service in Australia. This study is interesting because it included physiological measures of smoking to identify any compensatory smoking.

Subjects A screening question showed that 60 per cent (n = 47) of the employees were currently smoking. Twenty-four subjects (15 males and 9 females) completed all measures. They had an average age of 34 years, had smoked on average for 11 years and smoked on average 26 cigarettes a day.

Design The subjects completed a set of measures 1 week before the ban (time 1) and 1 (time 2) and 6 weeks (time 3) after.

Measures At times 1, 2 and 3, the subjects were evaluated for cigarette and alcohol consumption, demographic information (e.g. age), exhaled carbon monoxide and blood cotinine. The subjects also completed daily record cards for 5 working days and 2 non-working days, including measures of smoking, alcohol consumption, snack intake and ratings of subjective discomfort.

The results showed a reduction in self-reports of smoking in terms of number of cigarettes smoked during a working day and the number smoked during working hours at both the 1-week and 6-week follow-ups compared with baseline, indicating that the smokers were smoking less following the ban. However, although there was an initial reduction in nicotinine at week 1, by 6 weeks blood nicotine levels were almost back to baseline levels, suggesting that the smokers may have been compensating for the ban by smoking more outside the workplace. The results also showed reductions in craving and stress following the ban; these lower levels of stress were maintained, whereas craving gradually returned to baseline (supporting compensatory smoking). The results showed no increases in snack intake or alcohol consumption.

The self-report data from this study suggest that worksite bans may be an effective form of public health intervention for reducing smoking. However, the physiological data suggest that simply introducing a no smoking policy may not be sufficient, as smokers may show compensatory smoking.

Community-based programmes. In the Stanford Five City Project, the experimental groups received intensive face-to-face instruction on how to stop smoking and in addition were exposed to media information regarding smoking cessation. The results showed a 13 per cent reduction in smoking rates compared with the control group (Farquhar et al. 1990).

In the North Karelia Project, individuals in the target community received an intensive educational campaign and were compared with the members of a neighbouring community who were not exposed to the campaign. The results showed a 10 per cent reduction in smoking in men in North Karelia compared with men in the control region. In addition, the results also showed a 24 per cent decline in cardiovascular deaths, a rate twice that in the rest of the country (Puska et al. 1985). Other community-based programmes include the Australia North Coast Study, which resulted in a 15 per cent reduction in smoking over 3 years (Egger et al. 1983), and the Swiss National Research Programme, which resulted in a 8 per cent reduction over 3 years (Autorengruppe Nationales Forschungsprogramm 1984).

Government interventions.

- Restrictinglbanning

advertising.

- Increasing the cost. Research indicates a relationship between the cost of cigarettes and alcohol and their consumption.

- Banning smoking in public places. Smoking is already restricted to specific places in many countries (e.g. in the UK most public transport is no smoking). A wider ban on smoking may promote smoking-cessation. According to social learning theory, this would result in the cues to smoking (e.g. restaurants, bars) becoming eventually disassociated from smoking. However, it is possible that this would simply result in compensatory smoking in other places.

- Banning cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking. But the government loses tax and consumption is driven underground, just as drug-taking is. Also consider the unsuccessful prohibition era in the USA.

Methodological problems evaluating

clinical and public health

interventions

* Who has become a non-smoker? Someone who hasn't smoked in the last month/week/day? Someone who regards themselves as a non-smoker? (Smokers are notorious for under-reporting their smoking.) Does a puff of a cigarette count as smoking? Do cigars count as smoking? These questions need to be answered to assess success rates.

* Who is still counted as a smoker? Someone who has attended all clinic sessions and still smokes? Someone who dropped out of the sessions half-way through and hasn't been seen since? Someone who was asked to attend but never turned up? These questions need to be answered to derive a baseline number for the success rate.

* Should non-smokers be believed when they say they don't smoke? Methods other than self-report exist to assess smoking behaviour, such as carbon monoxide in the breath, cotinine in the saliva. These are more accurate but are time-consuming and expensive.

* How should smokers be assigned to different interventions? For success rates to be calculated, comparisons need to be made between different types of intervention (e.g. aversion therapy vs cue exposure). These groups should obviously be matched for age, gender, ethnicity and smoking behaviour. Subjects could be matched on what stage of change (contemplation vs precontemptation vs preparation) they are at, or on health beliefs such as self-efficacy, or costs and benefits of smoking. The list of items to match on is endless, but it is difficult to find subjects that match if many variables to match on are used.

Although

many people are successful at initially stopping smoking and changing their

drinking behaviour, relapse rates are high. Interestingly, the pattern for

relapse is consistent across a number of different addictive behaviours, with

high rates initially tapering off over a year.

Although

many people are successful at initially stopping smoking and changing their

drinking behaviour, relapse rates are high. Interestingly, the pattern for

relapse is consistent across a number of different addictive behaviours, with

high rates initially tapering off over a year.

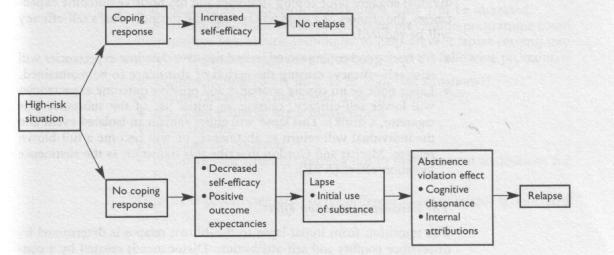

Marlatt and Gordon (1985) developed a relapse prevention model of addictions which specifically examined the processes involved in successful and unsuccessful cessation attempts. The relapse prevention model was based on the following concept of addictive behaviours:

* Addictive behaviours are learned and therefore can be unlearned; they are reversible.

* Addictions are not 'all or nothing' but exist on a continuum.

* Lapses from abstinence are likely and acceptable.

* Believing that 'one drink-a drunk' is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

They distinguished between a lapse, which entails a minor slip (e.g. a cigarette, a couple of drinks), and a relapse, which entails a return to former behaviour (e.g. smoking 20 cigarettes, getting drunk). Marlatt and Gordon examined the processes involved in the progression from abstinence to relapse and in particular assessed the mechanisms which may explain the transition from lapse to relapse

Baseline state

Baseline state

Abstinence - the target behaviour

Pre-lapse state

High-risk situation. External (pub) or internal (upset) cue to start smoking

Coping behaviour. e.g. eating instead

Positive outcome expectancies. According to previous experience, the individual will either have positive outcome expectancies if they carry out the behaviour (e.g. smoking will make me feel less anxious) or negative outcome expectancies (e.g. getting drunk will make me feel sick).

No lapse or lapse?

high risk situation, a good coping mechanisms and negative outcome expectancies (smoking will make me ill), the chances of a lapse will be reduced and the individual's self-efficacy will be increased. However, if poor coping strategies and has positive outcome expectancies (I will be less anxious if I smoke), the chances of a lapse will be high and the individual's self-efficacy will be reduced.

This lapse will either remain an isolated event and the individual will return to abstinence, or will become a full-blown relapse. Marlatt and Gordon describe this transition as the abstinence violation effect (AVE).

The abstinence violation effect

The transition from initial lapse to full-blown relapse is determined by dissonance conflict and self-attribution. Dissonance is created by a conflict between a self-image as someone who no longer smokes/drinks and the current behaviour (e.g. smoking/drinking). This conflict is exacerbated by a disease model of addictions which emphasizes 'all or nothing', and minimized by a social learning model which acknowledges the likelihood of lapses.

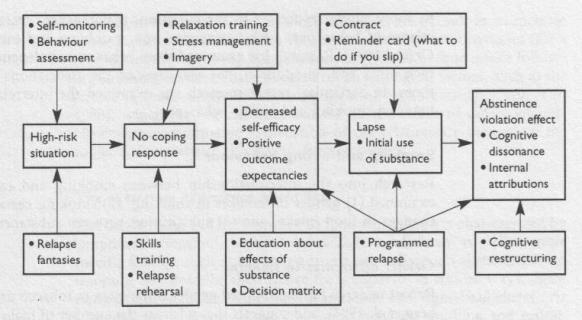

Relapse Prevention Programme

Relapse Prevention Programme

- Self-monitoring (What do I do in high risk situations)

- Relapse fantasies (What would it be like to relapse)

- Relaxation training / Stress Management

- Skills training

- Contingency contracts

- Cognitive restructuring (learning not to make internal attributions for relapse)

Family Therapy

Stanton and Shadish (1997), in a

meta-analysis of family therapy, reported on its superiority over other

modalities of treatment such as individual counselling or therapy, peer group

therapy, and family psychoeducation. There was inconclusive evidence to

demonstrate any particular “school'' of family therapy over another, partly

because of a dearth of research and much commonality between them. These positive

conclusions held for both the adult and the adolescent studies reviewed. With

the dearth of research evidence in adolescent treatment outcome, these results

are welcomed. The authors also reported the evidence on the cost-effectiveness

of family therapy. There was some evidence on the effectiveness of family

therapy approaches, both with fewer sessions required than with individual

therapy, but also with savings in social costs. Cost-effectiveness of these

treatment approaches merits significantly more attention.

More emphasis needs to be given

to gender differences and outcome research, particularly given the increased

recognition of drug and alcohol use in females.

Treatment concepts tend to

emphasise the importance of comprehensiveness, to include the treatment of drug

and alcohol-related behaviour as well as other comorbid and correlated

behaviours (Kazdin, 1987). These areas might include educational difficulties

and scholastic achievement, family conflict, parental substance use, and

involvement of other systems such as juvenile justice.

Characteristics and health status of individuals

The characteristics and health status of individuals entering smoking

cessation programmes may be an important moderator of their success. Cessation

rates are generally higher among those newly diagnosed with CHD in comparison

to still disease-free populations. In addition, those at particularly high risk

for disease may be more successful than others. Mcllvain et al. (1992), for example, repeated the MRFIT smoking cessation

protocol, which had previously been associated with abstinence rates of 40 per

cent at the four-year follow-up in a group of men in the highest decile of risk

for CHD, with a volunteer group of healthy persons. Although a high initial

abstinence rate was reported (52 per cent), this had fallen to 25 per cent by

the one-year follow-up — a

relatively good outcome, but not comparable with the original success of the

intervention. These facts support the

Health Belief Model’s assertion that perceived susceptibility is an influential

factor in deciding upon health behaviour.

A further factor which may powerfully influence the outcome of any

intervention is the emotional state of participants. Zelman et al. (1992), for example, reported

that 12 months following a smoking cessation course, 26 per cent of those who

evidenced some degree of depression at the time of the course were abstinent.

This contrasted with 62 per cent of those who were not depressed. They

suggested that negative affect may have disrupted either the initial

acquisition of coping skills during treatment or the generalization of those

skills beyond. These findings may generalize to other populations and

approaches. In a study of a community-wide stop smoking contest, Glasgow et al. (1985) also found perceived

stress to be a major determinant of outcome, with those highest on measures of

stress experiencing the least success in quitting.

Many smokers trying to quit do not use aids

Nearly 80 per cent of smokers who attempt to quit, do so

without using any method of

assistance, like nicotine replacement therapy (see: http://tinyurl.com/28k89) or

counselling (see: http://tinyurl.com/35n79).

Yet research shows that smokers who use

aids are twice as likely to achieve long-term abstinence from smoking. David

Hammond

(University of Waterloo, Ontario) and colleagues interviewed 616 adult smokers

over

the telephone to investigate why so few smokers use available aids to help them

stop

smoking.

It could be because they don't know about the available aids. Indeed, when

asked to

"list as many different methods...for quitting smoking as you can", a

third of

Hammond's sample failed to mention nicotine replacement therapies, and only

half

mentioned Zyban (see: http://tinyurl.com/39qkl),

an antidepressant known to help

people quit. At the same time, a quarter of participants mentioned an aid to

stopping

smoking for which there's no evidence of effectiveness, like hypnosis or

acupuncture.

There was also evidence that smokers don't believe available aids are

effective.

Nearly 80 per cent said they thought they would be as successful quitting on

their

own, as with help.

And failing to recognise the effectiveness of 'quitting aids' could be

undermining

smokers' attempts to stop. Three months after the initial telephone survey,

those

participants who had rated 'quitting aids' as effective, were twice as likely

to have

since made an attempt to quit.

There's "a need to balance health risk information with initiatives that

increase

awareness of cessation methods and their effectiveness: in addition to yelling

'fire!

', we must do a better job of leading smokers to the exit", the authors

said.

_______________________________________

Hammond, D., McDonald, P.W., Fong, G.T. & Borland, R. (2004). Do smokers

know how to

quit? Knowledge and perceived effectiveness of cessation assistance as

predictors of

cessation behaviour. Addiction, in Press.

Journal weblink: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/journals/add/

Action on smoking and health: http://www.ash.org.uk/

QUIT: http://www.quit.org.uk/

Acknowledgement

Paul

Bennett and Simon Murphy (1997), Psychology and Health Promotion, Open University

Press, 0-335-19766-3.