Theories of

Health Behaviour

Page 2

![]()

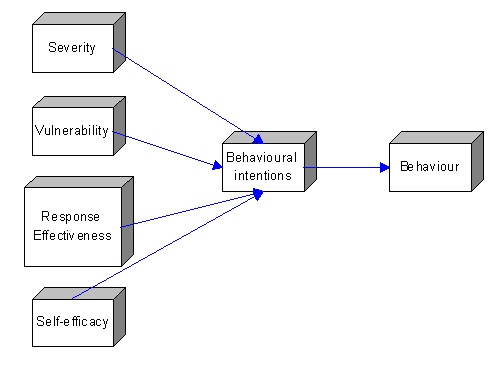

Protection motivation theory

Rogers (1975, 1983, 1985) developed protection motivation theory (PMT) which expanded the HBM to include additional factors.

Components of the PMT

Health-related behaviours are a product of five components:

Coping Appraisal

- self-efficacy (e.g. 'I am confident that I can change my diet');

- Response effectiveness (e.g. 'changing my diet would improve my health');

Threat Appraisal

- Severity (e.g. 'bowel cancer is a serious illness');

- Vulnerability (e.g. 'my chances of getting bowel cancer are high').

- Fear

According to the PMT, there are two sources of information:

1. environmental (e.g. verbal persuasion, observational learning) and

2. intrapersonal (e.g. prior experience).

This information elicits either an 'adaptive' coping response (i.e. the intention to improve one's health) or a 'maladaptive' coping response (e.g. avoidance, denial).

Support for the PMT

Rippetoe and Rogers (1987) gave women

information about breast cancer and examined the effect of this information on

the components of the PMT and their relationship to the women's intentions to

practise breast self-examination (BSE). The results showed that the best

predictors of intentions to practise BSE were response effectiveness (believing

that BSE would detect the early signs of cancer), severity (believing that

Breast cancer is dangerous and difficult to treat in it's advanced stages) and

self-efficacy (belief in one's ability to carry out BSE effectively).

In a further study, the effects of persuasive

appeals for increasing exercise on intentions to exercise were evaluated using

the components of the PMT. The results showed that vulnerability (ill health

would result from lack of exercise) and self-efficacy (believing in one's

ability to exercise effectively) predicted exercise intentions but that none of

the variables were related to self-reports of actual behaviour.

In a further study, Beck and Lund (1981)

manipulated dental students' beliefs about tooth decay using persuasive

communication. Their results showed that the information increased fear and

that severity (tooth decay has disastrous consequences) and self-efficacy (I

can do something about it) were related to behavioural intentions (flossing and

brushing regularly especially after eating).

Criticisms of the PMT

The PMT has been less widely criticized than the HBM; however, many of the criticisms of the HBM also relate to the PMT. For example, the PMT assumes that individuals are rational information processors (although it does include an element of irrationality in its fear component), it does not account for habitual behaviours, such as brushing teeth, nor does it include a role for social (what others do) and environmental factors (eg opportunities to exercise or eat properly at work). Schwarzer (1992) has also criticized the PMT for not tackling how attitudes might change (a problem with the HBM as well).

This study developed psychometric scales to measure the main components of R. W. Rogers' (1983) Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) along with a stage of change measure to examine exercise behaviour towards the prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD). The study was conducted with 2 representative community samples (N=800, aged 18 yrs or older) characteristic of high rates of CHD in New South Wales, Australia. It was found that overall, PMT's coping appraisal component of self-efficacy and response efficacy produced stronger positive significant associations with exercise outcome measures than the theory's threat components. It is concluded that health education should mainly focus on positive coping messages to motivate adults of the community to initiate and maintain exercise behaviour for the prevention of CHD. Plotnikoff,-Ronald-C; Higginbotham,-N Psychology,-Health-and-Medicine. 2002 Feb; Vol 7(1): 87-98

Social cognition models

Social cognition theory was developed by Bandura (1977, 1986) and suggests

that expectancies, incentives and social cognitions govern behaviour. Expectancies

include:

- Situation outcome expectancies: the expectancy that a behaviour may be dangerous (e.g. 'smoking can cause lung cancer').

- Outcome expectancies: the expectancy that behaviour can reduce the harm to health (e.g. 'stopping smoking can reduce the chances of lung cancer').

- Self-efficacy expectancies: the expectancy that the individual is capable of carrying out the desired behaviour (e.g. 'I can stop smoking if I want to').

The concept of incentives suggests that behaviour is governed by its consequences. For example, smoking behaviour may be reinforced by the experience of reduced anxiety, whereas a feeling of reassurance may reinforce having a cervical smear after a negative result.

Social cognitions involve normative beliefs (e.g. 'people who are important to me want me to stop smoking').

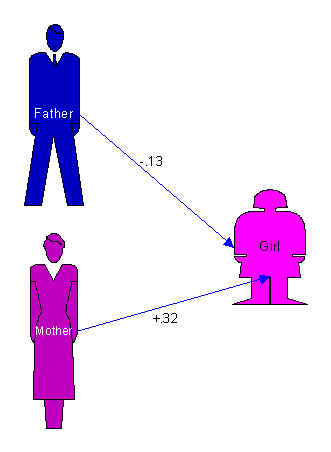

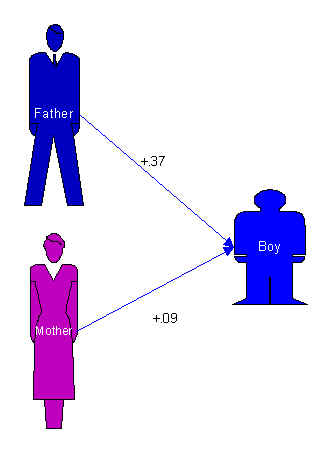

Parents have a strong influence over the health behaviours of children of the same sex with regard to Exercise, Smoking, Drinking, Eating and Sleep (Wickrama, Conger, Wallace and Elder, Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 1999).

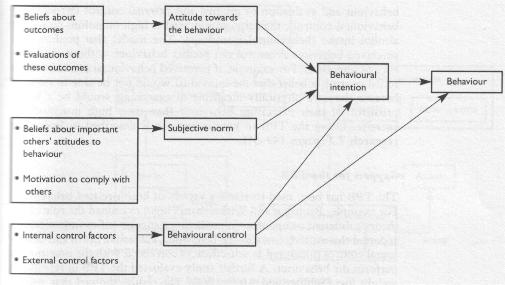

The theory of planned behaviour

The TPB emphasizes behavioural intentions as the outcome of a combination of several beliefs.

Intentions - 'plans of action in pursuit of behavioural goals' (Ajzen and Madden 1986) and are a result of the following beliefs:

1. Attitude towards a behaviour - positive or negative -(e.g. 'exercising is fun and will improve my health').

2.

Subjective norm - social pressure and motivation (e.g. 'people who are important to me will approve if

I lose weight and I want their approval').

3.

Perceived behavioural

control - self-efficacy and possible barriers

Support for the TPB

Povey et al (2000) studied the intentions of people to eat five portions of fruit and vegetables per day or to follow a low-fat diet. The TPB was good at predicting intentions but not behaviour. Self-efficacy was found to be a better predictor of behaviour.

Rutter (2000) studied women and whether or not they attended two breast-screening sessions separated by three years. Intention and first-time attendance was successfully predicted by the TPB. Attendance at the first session, however, was the best predictor of whether the woman attended three years later.

Brubaker and Wickersham (1990) examined the role of the theory's different components in predicting testicular self-examination and reported that attitude towards the behaviour, subjective norm and behavioural control (measured as self-efficacy) correlated with the intention to perform the behaviour.

TPB in relation to weight loss (Schifter and Ajzen 1985). The results showed that weight loss was predicted by the components of the model; in particular, goal attainment (weight loss) was linked to perceived behavioural control.

The present paper reports two studies designed to test the ability of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) to mediate the effects of age, gender and multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) on behavioural intentions and behaviour. Study 1 (N=124) employed a cross-sectional design and examined 3 self-reported health-related behaviours: safe sex (condom use), binge drinking and drink-driving. Study 2 (N=201) employed a prospective design and examined actual attendance at health screening. Respondents completed questionnaires measuring MHLC and TPB. Data were analysed using bivariate correlations and hierarchical multiple regression. Study 1 showed that the TPB was a superior predictor of health-related behavioural intentions than both demographic variables and MHLC. Study 2 corroborated the findings of Study 1, and showed that TPB variables were useful predictors of actual behaviour, although the TPB failed to fully mediate the effects of gender on screening attendance. While the TPB accounted for significant proportions of the variance in health-related behavioural intentions and behaviour, it failed to completely mediate the effects of demographic variables. Future work is required to identify social cognitive variables mediate the effects of demographics. Armitage,-Christopher-J; Norman,-Paul; Conner,-Mark British-Journal-of-Health-Psychology. 2002 Sep; Vol 7(3): 299-316

Criticisms of the TPB

Good

- Degree of irrationality

- Considers Social and Environmental factors

- Considers past behaviour within the measure of perceived behavioural control.

Bad

Schwarzer (1992) Ajzen does not describe either the order of the different beliefs or says what causes what (causality).

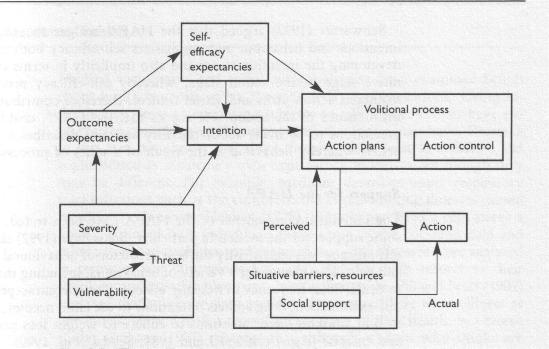

The health action process approach

The health action process approach (HAPA) was

developed by Schwarzer in 1992.

1.

it includes a temporal

element in the understanding of beliefs and behaviour.

2.

it emphasized the

importance of self efficacy

3. distinction between a decision-making/motivational stage and an action maintenance stage.

Components of the HAPA

According to the HAPA, the motivation stage is made up of the following components:

- self-efficacy (e.g. 'I am confident that I can stop smoking');

- outcome expectancies (e.g. 'stopping smoking will improve my health'), and a subset of social outcome expectancies (e.g. 'other people want me to stop smoking and if I stop smoking I will gain their approval');

- threat appraisal, which is composed of beliefs about the severity of an illness and perceptions of individual vulnerability.

The action stage is composed of:

A cognitive factor made up of action plans (e.g. 'if offered a cigarette when I am trying not to smoke I will imagine what the tar would do to my lungs') and action control (e.g. 'I can survive being offered a cigarette by reminding myself that I am a non-smoker').

The situational factor consists of social support (e.g. the existence of friends who encourage non-smoking) and the absence of situational barriers (e.g. financial support to join an exercise club).

Support for the HAPA

Schwarzer (1992) claimed that self-efficacy was consistently the best predictor of behavioural intentions and behaviour change for a variety of behaviours, including frequency of flossing, effective use of contraception self-examination, drug addicts' intentions to use clean needles, intentions to quit smoking, and intentions to adhere to weight loss programmes and exercise (e.g. Beck and Lund 1981; Seydal et al. 1990).

Surveyed 101 18-25 yr old male Australian university students to assess their testicular self-examination practices and knowledge of testicular cancer. A statistically significant difference was found in knowledge scores between performers and non-performers. The factors influencing performance of testicular self-examination were examined using R. Schwarzer's (1992) Health Action Process Approach as the theoretical framework. Results showed that the majority of men were uninformed or misinformed about testicular cancer and testicular self-examination. Eighty-three per cent of respondents did not perform testicular self-examination once per month as recommended. Intention, outcome expectancies and self-efficacy were the best predictors of testicular self-examination performance. Findings provided some support for the Health Action Process Approach. Barling,-Norman-R; Lehmann,-M Psychology,-Health-and-Medicine. 1999 Aug; Vol 4(3): 255-263

Criticisms of the HAPA

- Too rational - emotion is neglected

- The social and environmental influences are not considered as directly affecting behaviour, but rather as cognitions·

- Do these cognitive states exist or are they simply created cognitive theorists?

- The model attempts to combine components of the health belief model, the trans-theoretical model of change and the theory of planned behaviour.

Non-Rational processes

The defence mechanism of Denial

Cigarette smokers etc

Lay theories about health

Communication between health professional and patient would be redundant if the patient held beliefs about their health that were in conflict with those held by the professional.

Examined laypersons' perspectives of illness: the content of causal explanations of diabetes and differences in explanations according to gender. Qualitative research was carried out in Guadalajara, Mexico. A nonprobabilistic sample of 20 diabetic individuals (aged 35-71 yrs) participated in interviews, and the content of the interviews was analyzed. On the origin of their condition, participants offered explanations that match neither the biomedical model nor any other formal causal theory. Participants attributed the onset of diabetes to socioemotional circumstances linked to their life experiences and practices. Men attributed causality to work and social circumstances outside the home; women attributed it to family life and domestic circumstances. The authors discuss how lay theories can be useful for the reorganization of health services. Mercado-Martinez,-Francisco-J; Ramos-Herrera,-Igor-Martin Qualitative-Health-Research. 2002 Jul; Vol 12(6): 792-806

In a further study, Pill and Stott (1982) reported that working-class mothers were more likely to see illness as uncontrollable.

In a recent study, Graham (1987) reported that although women who smoke are aware of all the health risks of smoking, they report that smoking is necessary to their well-being and an essential means for coping with stress.

Blaxter (1990) analysed the definitions of health provided by over 9000 British adults in the health and lifestyles survey. She classified the responses into nine categories:

·

Health

as not-ill: the absence of physical symptoms.

·

Health

despite disease.

·

Health

as reserve: the presence of personal resources.

·

Health

as behaviour: the extent of healthy behaviour.

·

Health

as physical fitness.

·

Health

as vitality.

·

Health

as psycho-social well-being.

·

Health

as social relationships.

·

Health

as function.

It was found that there was considerable agreement in the emphasis on behavioural factors as causes of illness. There was however limited reference to structural or environmental factors, especially among those from working-class backgrounds. Gender differences were also found. The women were more likely to define health in terms of personal relationships. Murray and McMillan (1988) also found that working class women made repeated reference to their families when describing cancer.

Chamberlain (1997) noted a series of social class differences in his review of several studies of lay people’s perceptions of health. Lower social economic status people emphasise the role of health in their ability to work whereas higher social economic status people referred more to their ability to participate in leisure activities. Four different lay views of health emerged:

1. Lower social economic status participants only reported a view that emphasised physical aspects.

2. Both lower and higher social economic status participants gave a dualistic view in which physical and mental aspects of health were combined.

3. Predominantly higher social economic status gave a complimentary view of health, which integrated both physical and mental dimensions.

4. Higher social economic status participants gave a multiple view of health, which included physical, mental, emotional, social and spiritual directions.

Stainton-Rogers (1991) used Q-sort methodology to identify the concepts used by a sample of British adults to explain health. She identified eight different accounts of health and illness:

· The ‘body as machine’ account which considered illness as naturally occurring and ‘real’ with biomedicine considered the main form of treatment.

· The ‘body under siege’ account which considered illness as a result of external influences such as germs or stress.

· The ‘inequality of access’ account which emphasized the unequal access to modern medicine.

· The ‘cultural critique’ account which was based upon a sociological worldview of exploitation and oppression.

· The ‘health promotion’ account which recognized both individual and collective responsibility for ill health.

· The ‘robust individualism’ account which was concerned with every individual’s right to a satisfying life.

·

The ‘willpower account’ which defined health in terms

of the individuals ability to exert control.

Assumptions

in Health psychology

1.

Humans are rational in

their information processing. It is the role of perceived

factors (e.g. risk, rewards, costs, etc) rather than actual

risks.

2.

Different cognitions are

separate from and perform independently from each other. Could be because the

researchers ask questions relating to each 'type' of cognition.

3.

The types of cognition

may not really exist nor play a part in the patient's thinking about their

health; they could just be an artefact of the way the research was carried out.

4.

Cognitions are not

placed within a context. For example, actual social pressure and environment

are not taken into account, only the individual's interpretation of social pressure

and environmental influences.

Links