Click Here For

Latest Update Please

Theories of Health

Behaviour

Reading

Banyard, P., Applying Psychology to Health, Hodder & Stoughton, 1996, Chapter 6.

Curtis, A.J., Health Psychology, Routledge, 2000, Chapter 1.

Ogden, J., Health Psychology, Open University press, 1996, Chapter 2.

Sarafino, E.P., Health Psychology, Wiley, 1994, Chapter 6

Summaries of some theories - Click here

Attribution theory

Attribution theory emphasises attributions for causality and control.

Causes of disease

According to the basic

tenets of attribution theory people attempt to provide a causal explanation

for events in their world particularly if those events are unexpected and have

personal relevance (Heider, 1958). Thus it is not surprising that people will

generally seek a causal explanation for an illness, particularly one that is

serious.

According to the basic

tenets of attribution theory people attempt to provide a causal explanation

for events in their world particularly if those events are unexpected and have

personal relevance (Heider, 1958). Thus it is not surprising that people will

generally seek a causal explanation for an illness, particularly one that is

serious.

Taylor et al. (1984) interviewed a sample of women who had been treated

for breast cancer. They found that 95% of the women had a causal explanation for their cancer. These causes

were classified as stress (41%), specific carcinogen (32%), heredity (26%),

diet (17%), blow to breast (10%) and other (28%) (see bar chart). They also

asked the women who or what they considered responsible for the disease and

found that 41% of the women blamed themselves, 10% blamed another person, 28%

blamed the environment and 49% blamed chance (see bar chart below). The

patients were also asked whether they felt any control over their cancer and

they found 56% felt they had some control.

Weiner et al. (1972) suggested that we can classify attributional dimensions

along three dimensions:

·

1 Locus: the extent to which the cause is

localized inside or outside the person.

2 Controllability: the extent to which the person

has control over the cause.

3 Stability: the extent to which the cause

is stable or changeable.

How the person explains an event partly determines how that person

subsequently copes with that situation. Affleck et al. (1987) interviewed a

sample of men who had been hospitalised for a heart attack. The most common

causes for the heart attack were stress and personal behaviour. They found

that attributing the cause to stress (external, uncontrollable) was predictive

of greater morbidity over the following eight years (in other words, if you believe you have little control over

your illness you are more likely to get worse). According to Turnquist et al.

(1988) being able to identify a potential cause of an illness, irrespective of

the character of that cause, is an important predictor of subsequent

adjustment.

Brickman et al. (1982) points out that attributions are not just made about the causes of a problem but are also made about the possible solutions. For example an alcoholic may believe that his lack of will power is the cause of his drinking problem but he may also believe that the medical profession is responsible for making him well again.

Herzlich (1973) interviewed 80 people about the general causes of health and illness and found that health is regarded as internal to the individual and illness is seen as something that comes into the body from the external world.

Bradley (1985) perceived control over illness was related to diabetic's choice of treatment. Those patients choosing an insulin pump showed decreased control over their diabetes and increased control attributed to powerful doctors.

King (1982) found that individuals who believed that hypertension was external but controllable by the individual were more likely to attend a screening clinic.

Health Locus of control

Health locus of control, like attribution theory, also emphasises attributions for causality and control.

Wallston and Wallston (1982) developed a measure of the health locus of control, which evaluates whether individuals regard their health as controllable by them or not controllable by them or they believe their health is under the control of powerful others. Health locus of control is related to whether individuals changed their behaviour and to the kind of communications style they require from health professionals.

There are several problems with the concept of a health locus of control:

- Is health locus of control a fixed traits or a transient state?

- Is it possible to be both external and internal?

- Going to the doctor could be seen as external (the doctor is a powerful other) or internal (I am looking after my health).

Unrealistic optimism

Unrealistic optimism focuses on perceptions of susceptibility and risk.

Weinstein (1984) suggested that one of the reasons why people continued to practice unhealthy behaviours is due to inaccurate perceptions of risk and susceptibility - their unrealistic optimism. He asked subjects to examine a list of health problems and displayed what "compared to other people of your age and sex, are your chances of getting the problem greater than, about the same, or less than theirs?" Most subjects believed they were less likely to get the health problem.

Weinstein (1987) described four cognitive factors that contribute to unrealistic optimism:

1. Lack of personal experience with the problem

2. The belief that the problem is preventable by individual action

3. The belief that if the problem has not yet appeared, it will not appear in the future

4. The belief that the problem is infrequent.

It can be seen that the perception of own risk is not a rational process.

Weinstein (1983) individuals ignore their own risk increasing behaviour (I drink lots of alcohol but that's irrelevant) and focus on a risk reducing behaviour (but at least I don't smoke). In addition to this people are egocentric and therefore tend to ignore others risk decreasing behaviour (my friends drink in moderation but that's irrelevant).

Hoppe and Ogden (1996) heterosexual subjects were asked to complete a questionnaire concerning their beliefs about HIV and their sexual behaviour. Subjects were allocated to one of two conditions, risk increasing condition and risk decreasing condition. In the risk-increasing condition they were asked, "since being sexually active, how often have you asked about your partners HIV status?" It was found that few subjects would be able to answer that they had done this frequently and therefore would feel more risk. In the risk decreasing condition subjects were asked, "since being sexually active, how often have you tried to select your partners carefully?" It was thought that most people would answer this by saying that they did thus, making them feel less at risk. It was then found that those who focused on risk decreasing tended to increase their optimism because they thought others were more at risk.

This

study examined the relationship of dispositional, unrealistic, and comparative

optimism to each other and to personal risk beliefs, actual risk, and the

knowledge and processing of risk information. The study included 146 middle-age

adults (40-60 yrs old) who reported heart attack-related knowledge, beliefs,

and behaviors and read an essay about heart attack risk factors. Dispositional

optimism was correlated with comparative optimism (perception of low risk

relative to peers) but not with a variable assessing accuracy of participants'

comparative risk estimates (unrealistic optimism). Individuals high in dispositional

optimism and comparative optimism possessed an adaptive risk and belief profile

and knew more about heart attacks, whereas unrealistically optimistic

individuals exhibited the opposite pattern and also learned relatively less of

the essay material. Evidently, perceptions of low comparative risk are

relatively accurate, dispositional optimism is associated in an adaptive way

with information processing, and unrealistic optimism may be associated with processing

deficits and defensiveness, as well as higher risk.

Personality-and-Social-Psychology-Bulletin. 2002 Jun; Vol 28(6):

836-846

Radcliffe,-Nathan-M; Klein,-William-M-P

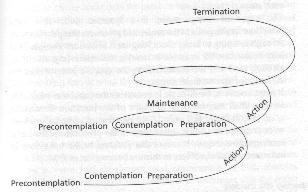

The transtheoretical model of behaviour change (stages of change model)

The transtheoretical model of change emphasises the dynamic nature of beliefs, time, and costs and benefits.

Prochaska and DiClemente (1982) proposed a model of behaviour change based on the following stages:

1. Precontemplation: not intending to make any changes

2. Contemplation: considering a change

3. Preparation: making small changes

4. Action: actively engaging in a new behaviour

5. Maintenance: sustaining change over time

Individuals would go through these stages in order but might also go back to earlier stages.

People in the later stages, e.g. maintenance, would tend to focus on the benefits (I feel healthier after giving up smoking), whereas people in the earlier stages tend to focus on the costs (I will be at a social disadvantage if I give up smoking).

Evaluation of stages of change model

Successful for smoking cessation, reduction in alcohol intake, exercise and cancer screening behaviour.

Takes account of the passage of time. Difficult to know what stage an individual is in. Prochaska et al (1992) Only ten to 15% of addicted smokers were prepared for action. Most in the pre-contemplative and contemplative stages.

Bandura (1997) argued that the stages are artificial and do not reflect the constant process of change. Prochaska and Velicer (1997) replied that the stages are not a substitute for processes but rather an attempt to specify when and where such processes operate. However, there still remains the concern that this model does not sufficiently consider the social aspects and meaning of smoking.

A relationship has been found between level of education and the stage of change reached when contemplating taking regular exercise. Those people with lower levels of education tended to be at an earlier stage of change (Booth et al. 1993), and therefore it could be argued that the model could be improved by taking account educational attainment in order to help predict the length of time a person is likely to remain at the earlier stages.

Provides data on stage distribution in 421 daily smokers (aged 16-79 yrs), tests the hypothesized discontinuity in patterns in assessments of pros, cons, and confidence between Ss at the precontemplation (PC) stage, the contemplation (C) stage, and the preparation (PA) stage, and compares the relative power of a stage measure and a more traditional 7-point intention measure in predicting assessments of pros, cons, and confidence. 60.9% of the Ss were in the PC stage, 30.3% in the C stage, and 8.7% in the PA stage. In accordance with what was expected, the pros of smoking outweighed the cons in the PC stage, while the cons of smoking outweighed the pros in the PA stage. Furthermore, the hypothesized contrasts in cons between stages were empirically supported, while those for confidence and pros of smoking were not supported by the data. Hence to the extent that discontinuity patterns indicate the existence of qualitatively different stages, the present data appear to support the existence of such stages. However, although there is support for the idea that PC may be considered as a genuine stage qualitatively distinct from the C and PA stages, the data do not support the notion the C and PA should be distinguished from each other as separate stages. Kraft,-Pal; Sutton,-Stephen-R; Reynolds,-Heather-McCreath Psychology-and-Health. 1999 May; Vol 14(3): 433-450

Cognitive or rational models

The health belief model and protection motivation theory are cognitive models that emphasise individual cognitions, not the social context of these cognitions. It is assumed that behaviours result from a rational weighing up of the potential costs and benefits of the behaviour.

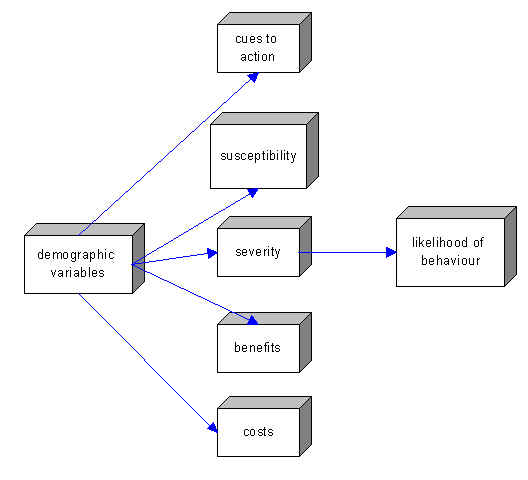

The Health Belief Model (Rosenstock 1966, revised by Becker et al)

The health-belief model considers three levels in predicting people's behaviour. The first thing that must be taken into account is the patient's readiness to act, or perception of the need for action. Such readiness is determined by the perceived severity of the disease state that exists or is likely to exist and the perceived susceptibility of the illness or its consequences. Thus, if patients don't believe that an illness is severe or that they themselves will become ill, readiness to act is low. Readiness to act is high if the obverse is true. For example, people are far more likely to get flu shots if they see the strain of flu that is expected as severe and highly contagious than if they think of it as mild and relatively rare.

The second set of considerations in this model involves estimation of costs and benefits of compliance. In order to comply, patients must believe that the regimen will be effective. They must also feel that the benefits of following it outweigh the costs. Consistent with reinforcement theories, compliance occurs only when the incentives for accepting doctors' orders are greater than those for not doing so.

Finally, the health-belief model includes a cue to action, something that makes the subject aware of potential consequences. Internal signals that something is wrong (pain, discomfort) or external stimuli such as health campaigns or screening programs are necessary to set in motion the analyses listed above. Demographic variables are also included, though they have not shown any systematic relation to compliance.

Support for individual components of the model.

Norman and Fitter (1989) examined health behaviour screening (for example breast cervical cancer) and found that perceived barriers (the costs of attending) were the greatest predictors of whether a person attended the clinic. Several studies have examined breast self-examination (BSE) behaviour and report that barriers (Lashley 1987; Wyper 1990) and perceived susceptibility (the likelihood of having the illness) (Wyper 1990) are the best predictors of healthy behaviour.

The role of giving information as a cue to action has been researched. Information in the form of fear-arousing warnings may change attitudes and health behaviour in such areas as dental health, safe driving and smoking (e.g. Sutton 1982; Sutton and Hallett 1989). Giving information about the bad effects of smoking is also effective in preventing smoking and in getting people to give up (e.g. Sutton 1982; Flay 1985). Several studies report a significant relationship between people knowing about an illness and their taking precautions. Rimer et al. (1991) report that knowledge about breast cancer is related to having regular mammograms. Several studies have also indicated a positive correlation between knowledge about BSE (Breast Self-examination) and breast cancer and performing BSE (Alagna and Reddy 1984; Lashley 1987; Champion 1990). Showing subjects a video about pap tests for cervical cancer was related to their actually having the pap test (O'Brien and Lee 1990'.)

Evidence Against

Janz and Becker (1984) found that healthy behavioural intentions are related to low perceived seriousness - not high as predicted (e.g. healthy adult having a flu injection) - and several studies have suggested an association between low susceptibility (not high) and healthy behaviour (e.g. many students recently have agreed to be inoculated against meningitis) (Becker et al. 1975; Langlie 1977). Hill et al. (1985) applied the HBM to cervical cancer, to examine which factors predicted cervical screening behaviour. Their results suggested that benefits and perceived seriousness were not related. Janz and Becker (1984) carried out a study using the HBM and found the best predictors of health behaviour to be perceived barriers and perceived susceptibility to illness. However, Becker and Rosenstock (1984), in a review of 19 studies using a meta-analysis that included measures of the HBM to predict compliance, calculated that the best predictors of compliance are the costs and benefits and the perceived seriousness. So there is lack of agreement over what really does help to predict health behaviour.

Criticisms of the HBM

- Is health behaviour that rational? (Is tooth-brushing really determined by weighing up the pros and cons?).

- Its emphasis on the individual (HBM ignores social and economic factors)

- The measurement of each component

- The absence of a role for emotional factors such as fear and denial.

- It has been suggested that alternative factors may predict health behaviour, such as outcome expectancy (whether the person feels they will be healthier as a result of their behaviour) and self-efficacy (the person’s belief in their ability to carry out preventative behaviour) (Seydel et al. 1990; Schwarzer 1992).

- Schwarzer (1992) has further criticized the HBM for saying nothing about how attitudes might change.

- Leventhal et al. (1985) have argued that health-related behaviour is related more to the way in which people interpret their symptoms (e.g. if you feel unwell and you feel it is not going to cure itself then you would probably do something about it).

The revised HBM

Becker and Rosenstock (1987) have revised the HBM and have described their new model as consisting of the following factors:

- the existence of sufficient motivation;

- the belief that one is susceptible or vulnerable to a serious problem;

- and the belief that change following a health recommendation would be beneficial to the individual at a level of acceptable cost.

![]()