Lifestyles and Health

Reading

Banyard, P., Psychology in Practice

– Health, Hodder & Stoughton, 2002, Ch 7 (ISBN 0-340-84496-5)

Curtis, A.J., Health Psychology,

Routledge, 2000, Chapter 7.

Harari, P. and Legge, K, Psychology and Health, Heinemann, 2001, Ch 1.

David F. Marks et al, 2000, Health Psychology, Sage, 0-8039-7608-9.

Dawn K Wilson et al (Eds.) 1997, Health promoting and health compromising behaviours among the minority adolescents, American psychological association, 1-55798-397-6.

What are health behaviours?

Kasl and Cobb

(1966) defined three types of health related behaviours. They suggested that;

- a health behaviour is a behaviour aimed

at preventing disease (e.g. eating a healthy diet);

- an illness behaviour is a behaviour

aimed at seeking a remedy (e.g. going to the doctor);

- a sick role behaviour is an activity

aimed at getting well (e.g. taking prescribed medication or resting).

Health behaviours

have also being defined by Matarazzo (1984) in terms of either:

Health impairing

habits, which he called "behavioural pathogens" (for example smoking,

eating a high fat diet), or

Health protective

behaviours, which he defined as "behavioural immunogens" (e.g.

attending a health check).

Behaviour and

mortality

50% of mortality

from the 10 leading causes of death is due to behaviour Doll and Peto (1981)

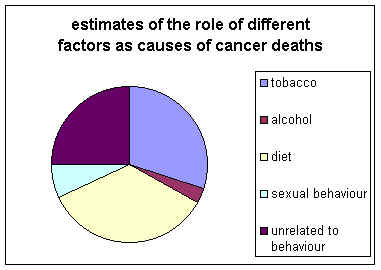

estimated that 75% of cancer deaths were related to behaviour (see pie chart).

90% of all lung cancer mortality is attributable to cigarette smoking, which is

also linked to other illnesses such as cancers of the bladder, pancreas, mouth,

and oesophagus and coronary heart disease. Bowel cancer is linked to behaviours

such as a diet high in total fat, high in meat and low in fibre.

Doll and Peto (1981)

estimated that 75% of cancer deaths were related to behaviour (see pie chart).

90% of all lung cancer mortality is attributable to cigarette smoking, which is

also linked to other illnesses such as cancers of the bladder, pancreas, mouth,

and oesophagus and coronary heart disease. Bowel cancer is linked to behaviours

such as a diet high in total fat, high in meat and low in fibre.

Latest news on

cancer December 2001

Psychosocial

mediators of health

Lifestyle and health

About 50% of premature deaths in western countries can be attributed to lifestyle (Hamburg et al., 1982). Smokers, on average, reduce their life expectancy by five years and individuals who lead a sedentary (i.e. none active) lifestyle by two to three years (Bennett and Murphy, 1997).

Doll and Peto's Model

In

1951, 34,440 men replied to a questionnaire about their smoking habits1.

These men were all members of the British Medical Association. In the

following twenty years, 10,072 deaths occurred in the population. Any changes

in smoking habits were noted in follow-up questionnaires. The purpose of

this prospective cohort was to investigate the relationship between smoking and

cause of death. The primary effects the investigators found included

increased heart disease, lung cancer, chronic destructive lung disease, and

various vascular diseases. Of those who died from lung cancer during

follow-up, death certificates were reviewed. Also, the medical

practitioners responsible for identifying the cause of death were interviewed.

When questions remained as to whether lung cancer was the cause of death, a

professor of medicine, who was blind to the individual's smoking status,

advised the investigator. Four hundred forty-one carcinomas of the lung

were accepted as the underlying cause of death. Lung cancer was a

contributory cause in an additional seventeen cases.

Doll

and Peto were interested in developing a model to analyze the lung cancer

incidence2. However, the investigators chose to include only

those men whose smoking status did not change. Therefore, changes in

smoking habits greater than five cigarettes per day resulted in

exclusion. Those smokers who began smoking between the ages of 16 and 25

and who smoked less than or equal to forty cigarettes a day were included.

Men who smoked more than forty cigarettes a day and men over the age of eighty

were excluded. There were 201 observed lung cancer incidences used in

developing this model.

|

Cigarettes per day

|

Mean |

Observed number of

|

|

0 |

0.0 |

6 |

|

1-4 |

2.7 |

3 |

|

5-9 |

6.6 |

4 |

|

10-14 |

11.3 |

16 |

|

15-19 |

16.0 |

18 |

|

20-24 |

20.4 |

58 |

|

25-29 |

25.4 |

30 |

|

30-34 |

30.2 |

36 |

|

35-40 |

38.0 |

30 |

|

TOTAL |

10.7 |

201 |

Four behaviours in particular are associated with disease: smoking, alcohol misuse, poor nutrition and lower levels of exercise; these are called the “holy four”. Conversely, rarely eating between meals, sleeping for seven to eight hours each night, and eating breakfast nearly every day have been associated with good health and longevity (Breslow and Enstrom 1980). Recently high-risk sexual activity has been added to the risk factor list.

In this country saturated fatty acids, full fat milk and red meat are being replaced with low saturated fats, semi skimmed milk and white meat.

Belloc and Breslow (1972) conducted an epidemiological study asking a representative sample of 6928 residents of Almeida County, California whether they engaged in the following seven health practises:

- sleeping seven to eight hours daily

- eating breakfast almost every day

- never or rarely eating between meals

- currently being at or near prescribed height adjusted weight

- never smoking cigarettes

- moderate or no use of alcohol

- regular physical activity.

People aged over 75 who carried out all of these health behaviours had health that was compatible to those aged 35-44 who followed less than 3 of the health behaviours.

Good health practice is associated with good health and this association was independent of age, sex and economic status (Belloc & Breslow, 1972). Follow-up studies after five and half years and nine and half years showed that good health practice is associated with longevity.

Men who followed all seven of these health practises had a mortality rate that was only 28% of that for men who followed three or less of these practises. For women, the difference was smaller: mortality rates for those who followed all seven practises was only 43% of that for women who followed three or less practises.

Kristiansen (1985) found that health behaviours were correlated with

- A high value on health,

- A belief in world peace,

- A low value on an exciting life.

Leventhal et al (1985) described factors that they believed predicted health behaviours:

- Social factors, such as learning reinforcement, modelling and social norms;

- Genetics

- Emotional factors, such as anxiety, stress, tension and fear;

- Perceived symptoms, such as pain breathlessness and fatigue;

- The beliefs of the patient;

- The beliefs of the health professionals.

Taking a combination of these factors might enable us to predict and promotes health-related behaviour.

Having a positive attitude towards life has been

found to increase longevity (Levy

et al, 2002). The team

used data gathered in 1975 in Oxford, Ohio, where almost everybody over 50 was

questioned about their life and health. By tracing the deaths of participants

over 23 years, the team was able to match lifespan against attitudes towards

ageing expressed at the start.

Participants had been asked to agree or disagree with statements

such as: “Things keep getting worse as I get older” or “I have as much pep as I

did last year” or “I am as happy now as I was when I was younger.” The

participants were scored on a scale of zero to five, in which five represented

the most positive attitude towards growing older and zero the most negative.

In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the team

says that the median survival for the most negative thinkers was 15 years, while

for the most positive it was 22.5 years.

Controlling for age, sex, wealth, health and loneliness did not alter the finding.

Evaluation

• There are several methodological criticisms that can be made of the original study by Belloc and Breslow and the follow-up studies. First, the sample is not particularly representative as all the participants came from the same area in the USA. Second, the study establishes a correlation between seven specific health preventive behaviours and longevity, but does not prove that these behaviours actually caused some of the participants to live longer. It is possible, although unlikely, that some other factor — personality, for example — affected both behaviour and lifespan. The ‘behavioural change’ approach to promoting health raises a couple of ethical issues. First, it can lead to ‘victim-blaming’. If we believe too strongly that individuals can prevent themselves from falling ill by choosing to carry out health preventive behaviours, then we may go on to blame those individuals for failing to protect their own health if they do fall ill.

There have been cases where doctors have refused to treat certain patients because they felt that they had brought their illnesses on themselves. The greatest contributions to health have been through developments in medical science and through public health initiatives such as improved sanitation, and not through individual behavioural change.

The second problem with the behavioural change approach is the narrow line that exists between persuading someone to change his or her behaviour and coercion. Do we have a right to assume that we know better than someone else what is best for their own health, and to force them to change their behaviour?

Genetic theories

Genetics has an obvious impact on people’s health in the sense that many diseases have genetic components. It is rarely the case that an individual’s genetic inheritance actually determines his or her state of health, rather that some people are born with a genetic disposition towards certain conditions. Such people are more likely than others to develop a particular condition, but whether they actually do or not depends on environmental and behavioural factors.

It is possible for genetic disposition towards a particular condition to have an indirect impact on health preventive behaviour. For example, a woman whose mother and grandmother had breast cancer may be more likely to examine her own breasts for lumps because she feels that she is more susceptible to the disease than average.

Is it possible, however, for a person’s genetic inheritance to directly affect their health-related behaviour? It may be, for example, that alcoholism is partly hereditary. In his book on this topic, Sher (1991) describes evidence that the children of alcoholics are more likely to become alcoholic themselves.

Although it is notoriously difficult to determine whether a correlation such as this is due to genetic factors or arises as a result of social learning, some psychologists argue that, although there probably is no such thing as an ‘alcoholism gene’, certain genetically inherited personality traits may pre-dispose an individual towards alcohol abuse.

The link between genes and alcoholism may be even subtler. Richard Burton, the famous actor, was once quoted as saying that he would never have become an alcoholic if he had ever suffered a hangover. The ability to drink heavily without getting a headache the following morning may well be linked to the way the body metabolises alcohol, and this may be partly affected by genetic inheritance.

Preliminary evidence has suggested

that family history of dietary risk factors is important for understanding

adolescent food preferences. Other genetic or biological influences may be

accounted for by ethnicity, body size, and gender. Although the evidence

presented next suggests a genetic role for understanding eating behaviors among

adolescents, environmental and individual differences are also important and

may interact with genetic influences in complex ways.

Family genetics and history of dietary risk factors. Several studies have provided

evidence that family history of dietary risk factors may be related to

adolescents’ food preferences. Fischer and Dyer (1981) reported that family

history of obesity was related to increased intake of sweets, dairy products,

and fatty foods in a sample of 116 high school girls. Their results also

indicated that having a family history of heart problems was related to

decreased consumption of milk, eggs, and salty foods. Levine, Lewy, and New

(1976) found a family history of hypertension to be associated with a greater

prevalence of obesity among African American adolescents. Some investigators

have also analyzed dietary intake among twin populations as evidence of a genetic

variance for nutrient intake. In one of these studies, De Castro (1993) found

significant heritabilities for identical and fraternal twins with regard to the

amount of food energy and macronutrients eaten daily. In contrast, Fabsitz,

Garrison, Feinleib, and Hjortland (1978) demonstrated that, in addition to a

genetic variance, environmental effects (e.g., how frequently twins saw each

other) were important in accounting for similarities in twins’ nutrient

intakes. These results suggest that there may be an interaction between

genetic and environmental factors that influence eating behaviors among

adolescents.

Genetic theories suggest that there may be a genetic predisposition to becoming an alcoholic or a smoker. To examine the influences of genetics, researchers have examined either identical twins reared apart or the relationship between adoptees and their biological parents. These methodologies tease apart the separate effects of environment and genetics. In an early study on genetics and smoking, Sheilds (1962) reported that of 42 twins reared apart, only 9 were discordant (showed different smoking behaviour). He reported that 18 pairs were both non-smokers and 15 pairs were both smokers. This is a much higher rate of concordance than predicted by chance. Evidence for a genetic factor in smoking has also been reported by Eysenck (1990) and in an Australian study examining the role of genetics in both the uptake of smoking (initiation) and committed smoking (maintenance) (Murray et al. 1985). Research into the role of genetics in alcoholism has been more extensive and reviews of this literature can be found elsewhere (Peele 1984; Schuckit 1985). However, it has been estimated that a male child may be up to four times more likely to develop alcoholism if he has a biological parent who is an alcoholic.

Commentary

Among all the theories described, this is the only one that comes down

firmly on the ‘nature’ side of the nature-nurture debate. All the others

explain difference in behaviour between individuals in terms of social or

environmental influences. However, even the most hard-line bio psychologist

would accept that health-related behaviour is not completely determined by

genetic inheritance; the most that genetics can do is to pre-dispose an

individual towards a particular behaviour.

Behaviourist learning

theories

Classical conditioning is a process in which the

individual associates an automatic response with a neutral stimulus. Ivan

Pavlov (1849—1936) described this process after he noticed that laboratory

dogs would salivate when he turned a light on because they had learnt to

associate the light with the presence of food.

Classical conditioning could explain certain health-related behaviours

such as ‘comfort eating’, for example. If a parent regularly offers a child

sweets or chocolate at the same time as physical and emotional affection, then

the child may learn to associate sweet foods with the reassuring feelings that

arise out of parental love. In later life, the child may try to recreate these pleasant

feelings by eating chocolate when he or she is stressed or depressed.

Operant conditioning is when people respond to

reward or punishment by either repeating a particular behaviour, or else

stopping it. If an individual carries out

a behaviour that clearly seems to be bad for his or her health, such as smoking

cigarettes, a deeper look may well reveal benefits for the individual, such as

social approval, the nicotine buzz and so on.

A striking example of how

operant conditioning can affect health behaviour is the study by Gil et al (1988). They conducted research on

children suffering from a chronic skin disorder that causes severe itching.

They videotaped the children with their parents in the hospital and observed

that when parents tried to stop their children scratching (in order to prevent peeling and

infection) this actually increased the scratching behaviour by rewarding it with attention. When they

asked parents to ignore their children when they scratched and give them

positive attention when they did not scratch, the amount of scratching was

significantly reduced.

Drinking, eating, smoking, drug and sexual addictions all have the

‘irrational’ characteristic that the total amount of pleasure gained from the

addiction seems much less than the suffering caused by it. According to

learning theorists, the reason for this lies in the nature of the gradient of

reinforcement. Addictive behaviours are typically those in which pleasurable

effects occur rapidly after the addictive behaviour while unpleasant

consequences occur after a delay. The simple mechanism of operant conditioning

and the gradient of reinforcement is able, as it were, to overpower the mind’s

capacity for rational calculation.

Social learning occurs when an individual

observes and imitates another person’s behaviour, either because the individual

looks up to that person as a role model or else through vicarious reinforcement — that is, .the individual sees the person being rewarded for his or her

actions. See Bandura. Social learning can clearly

be very influential in encouraging people to do things that are bad for their

health (for example, a teenager may take up smoking because he or she has an

admired elder brother who smokes, or may try illegal drugs because he or she

sees other people taking them and having a good time).

Another example of how vicarious reinforcement can lead to unhealthy

behaviour concerns young women with eating disorders, who see images of very

thin models in magazines being rewarded with success, money, glamour and fame.

On the other hand, many health promotion campaigns use positive role models to

try to get people to lead healthier lifestyles. The advertising industry,

whose reason for existing is to persuade people to change their behaviour,

often depicts successful, good-looking and happy people using a certain

product in the hope that this will make others want to use the product as well.

Bandura (1977) has been particularly influential in emphasising the

importance of learning by imitation in linking it is concept of self-efficacy,

personality traits consisting of having confidence in one’s ability to carry

out one’s plans successfully. People

with lower self-efficacy are much more likely to imitate undesirable behaviours

than those with higher self-efficacy.

Heather and Robertson (1997) give a useful discussion of the application

of these principles to drinking.

Patterns of drinking by parents are observed by children who may then

imitate them in later life, especially the behaviour of the same sex

parents. In adolescence, the drinking

behaviour of respected older peers may also be imitated, and subsequently that

of higher status colleagues at work, a phenomena, which may explain the

prevalence of heavy drinking in certain professions such as medicine and

journalism.

Commentary

Many psychologists criticize

behaviourist-learning theories on the grounds that they are too mechanistic. In other words, they

assume that human beings respond automatically to specific situations. Not only

does this imply a lack of freewill, but also it also ignores the effect on behaviour

of cognitive factors.

Social and environmental

factors

There are many different

social and environmental factors contributing to people’s health behaviour. For

example, a common explanation for young people taking drugs or smoking

cigarettes is ‘peer pressure’. It may be that people imitate their peers

because of the explanation given above — that is, vicarious reinforcement; they see others getting a reward for

a certain behaviour, so they copy it.

Social factors such as culture influence dietary behaviour. Culture affects an individual’s food

selection, preparation, and eating patterns.

Certain tastes or food are associated with specific feelings and

meanings within a culture (for example, soul food may denote fried and

barbecue meats within the African American community). Mexican American women often feel

uncomfortable with focusing on themselves as individuals therefore a successful

approach to losing weight would target the whole family rather than the

individual woman (Foreyt et al, 1991).

Television advertising also exerts a larger influence over dietary

behaviour. Advertisers often target

adolescents by promoting fast foods high in fact, cholesterol, sodium, and

sugar. It has been found that

children’s television viewing positively correlates with smoking behaviour and

attempts to influence parents shopping selections (Dietz and Gortmaker,

1985). Television viewing is also

highly correlated with obesity in children (Bowen et al, 1991).

Commentary

• Conformity does not exert an equally strong

influence in all situations and with all individuals, It is likely to be more

powerful in ambiguous situations, when others are perceived as having more

expertise, or when the individual has low self-confidence, poor self-esteem and

a weak sense of self-efficacy.

![]()

High-risk sexual behaviour

By the beginning of 1992, nearly two and a half million people had died of AIDS worldwide and 19 and a half million were known to be HIV positive. UK figures indicate a marked increase in the prevalence of other sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies. There is evidence of the higher prevalence of un-safe sex practices and perhaps harrowing future increases of HIV infection and AIDS. Adolescents heterosexuals form an increasingly at risk group for AIDS, accounting for about 20% of all newly reported cases in the USA (Stiff et al. 1990). Young women and ethnic minorities appeared to be at particular risk. AIDS related illnesses form the leading cause of death for young women aged 25 to 34 in the USA and the third leading cause for those between 15 and 19 years old. Ethnic minority adolescents, the majority of whom were poor urban blacks, accounted for 53% of new AIDS cases. A similar picture is emerging in the UK. Although the majority of newly diagnosed cases of AIDS are still gay and bisexual men, the incidence of new cases among this group is falling slowly as the incidence of such cases among the heterosexual community rises more rapidly. Adolescent sexual behaviour places many at high risk for disease, as they are a highly sexually active group. The findings from a British survey, for example, revealed that nearly half adolescents aged between 16 and 17 have had at least one sexual partner during the previous year. However, they are unlikely to plan intercourse and only half use any form of contraception. Hawkins et al. (1995) reported that the most frequent safer sex behaviour amongst well-educated heterosexual students was the use of the contraceptive pill. The least frequent sexual practice, reported by only 24% of the sample, was the use of condoms. An important factor is that the majority of young persons do not see themselves as at risk of HIV infection or have feelings of invulnerability towards the disease.

Exercise

Those who are physically active throughout the adult life live longer than those who are sedentary. Paffenburger et al (1986) monitored leisure time activity in a cohort of 17000 Harvard graduates dating back to 1916. Using questionnaires it was found that those who were least active after graduation had a 64% increased risk of heart attack compared with their more energetic classmates. Those who expended more than 2000 calories of energy in active leisure activities per week lived, on average, two and a half years longer than those classified as inactive. Exercise is protective against both chronic heart disease and some cancers (Blair et al 1986). How this protection is achieved, whether through short intense periods of exercise or longer more frequent less intense periods appears irrelevant and no additional health gain is achieved by exceeding these limits.

About a quarter of the UK population engage in health promoting levels of exercise, with a similar picture in the USA. In recent years these levels have dramatically increased. For example in Wales 20% of men and 2% of women took sufficient exercise in 1985 but by 1990 this had increased to 27% of the population. Those who engage in exercise are more likely to be young, male and well-educated adults, members of higher socio-economic groups, and those who have exercised in the past. Those least likely to exercise tend to be in the lower socio-economic groups, older individuals, and those whose health is likely to be at risk as a consequence of being overweight and smoking cigarettes (Dishman 1982). Obstacles to exercise include not having enough time, lack of support from family or friends and perceived incapacity due to ageing.

Brannon & Feist (1997) describe five different types of exercise.

- Isometric exercise involves pushing the muscles hard against each other or against an immovable object. The exercise strengthens muscle groups but is not effective for overall conditioning.

- Isotonic exercise involves the contraction of muscles and the movement of joints, as in weight lifting. Muscle strength and endurance may be improved but the general improvement is in body appearance rather than improving fitness and health.

- Isokinetic exercise uses specialised equipment that requires exertion for lifting and additional effort to return to the starting position. This exercise is more effective than both isometric and isotonic exercise and promotes muscle strength and muscle endurance (Pipes and Wilmore, 1975).

- Anaerobic exercise involves short, intensive bursts of energy without an increased amount of oxygen such as in short distance running. Such exercises improve speed and endurance but do not increase the fitness of the coronary and respiratory systems and indeed may be dangerous for people with coronary heart disease.

- Aerobic exercise requires dramatically increased oxygen consumption over an extended period of time such as in jogging, walking, dancing, rope skipping, swimming and cycling. The heart rate must be in a certain range which is computed from a formula based on age and the maximum possible heart rate. The heart rate should stay at this elevated level for at least 12 minutes, and preferably 15 to 30 minutes. This exercise improves the respiratory system and the coronary system. It is best to have a medical examination before starting a programme of aerobic exercise and an electrocardiogram (ECG) can detect abnormal cardiac activity during exercise.

Overall fitness includes measures of muscle strength, muscle endurance, flexibility and cardiovascular (aerobic) fitness. Each of the five types of exercise described above contributes to these different types of fitness although no one type of exercise fulfils all of these requirements.

Kuntzleman (1978)

- Organic fitness-our capacity for action and movement determined by inherent factors such as genes, age and health status.

- Dynamic fitness-determined by our experience.

Exercise helps to control our weight and improve our body composition by increasing our muscle tissue. This improves the ratio of fat to muscle for our bodies and helps us to sculptor a more ideal body. Exercise is at least as good as dieting if not better. Exercising retains more leaner muscle tissue whilst dieting loses both fat and lean tissue.

Exercise protects against coronary heart disease (C. H. D.).Cooper (1982) maintains that aerobic exercise should be performed at 70 to 85% of maximal heart rate non-stop for at least 12 minutes three times per week in order to improve cardiovascular system fitness.

Lakka et al. (1994) conducted a large scale five-year longitudinal study of middle-aged men. Results showed that men with high aerobic fitness were up to 25% less likely to suffer a heart attack compared with those with the low aerobic fitness.

Maurice et al. (1953) studied London double decker bus drivers and their conductors. The more active conductors had significantly less incidence of C. H. D. than did the sedentary drivers. Can you think of any confounding factors in this study?

Brannon and Feist (1997) have found that regular physical exercise gives protection against stroke and improves the ratio of high density lipoproteins (H. D. L.) to low density lipoproteins (L. D. L.) (this translates as good and bad cholesterol levels respectively). This also reduces the risk of heart disease and protects against some forms of cancer. Regular physical exercise also prevents bone density loss and helps to control diabetes.

There are psychological benefits to exercising including decreased depression, reduced anxiety, providing a buffer against stress and increased self-esteem and well-being.

Exercise has been found to lower depressive moods in a variety of people, including young pregnant women from ethnically diverse backgrounds (Koniak-Griffin, 1994) and nursing home residents aged 66 to 97 (Ruuskanen and Parkatti, 1994). These findings could be due to the release of endogenous Opiates during exercise.

Exercise helps to reduce state anxiety (a temporary feeling of dread arising from a social situation). It is not clear whether exercise can influence trait anxiety (changing your personality so that you are less anxious). Both exercise and relaxation reduced anxiety. This may be because the change of pace reduces anxiety. Norvell and Belles (1993) showed how combining a non-aerobic weight training course with an opportunity to train away from the pressures of work resulted in significant increases in psychological health, including lowered anxiety levels. Both aerobic and non-aerobic exercise have been found to help people cope with anxiety, with even a single session having a positive effect on alleviating depression, fatigue and anger (Pierce and Pate, 1994).

Exercise is a buffer against stress. This could be because of the positive effect on the immune system. Exercise produces a rise in natural killer cell activity and an increase in the percentage of T-cells (lymphocytes) that bear natural killer cell markers (indicating the sites where killer cells are produced). This warns off invading cells before they have the chance to harm the body. Both exercise and stress reduce adrenaline and other hormones yet exercise has a beneficial effect on heart functioning whereas stress may produce lesions in heart tissue. In exercise adrenaline metabolises differently and is released infrequently and gradually under conditions for which it was intended (e.g. jogging). In conditions of stress adrenaline is discharged in a chronic and enhanced manner.

Sinyor et al. (1986) failed to find any significant stress buffering benefit for stress in healthy young men who began an aerobic exercise programme or a weight lifting intervention. Whereas Roth and Holmes (1985) found that college students who engaged in physical exercise reported fewer stress related health problems and depressive symptoms than did less active college students. However this effect was only found for students with high stress and low fitness, students with low stress to begin with did not have such poor health. So a combination of high stress and low fitness seems to produce poor health.

Sonstroem (1984) in a meta-analysis found a significant positive relationship between exercise and self esteem. Hogan (1989) has found a relationship between fitness and self-confidence and self discipline. Ross and Hayes (1988) have demonstrated a relationship between subjective physical health and psychological well-being.

Over exercising naturally can produce poor health or even death from at risk individuals who are not closely supervised (Brannon and Feist, 1997).

Nutrition: diet and health

Dietary habits

The MRFIT study (Stamler et al. 1986), was a longitudinal study over six years of three hundred and fifty thousand adults. A linear relationship was found between blood cholesterol level and the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) or stroke. The risk for individuals within the top third of cholesterol levels was three and a half times greater than those in the lowest third. A 24 year longitudinal study of American men working for western electricity found that men who consumed high levels of cholesterol were twice as likely to develop lung cancer compared with men who consumed low levels of cholesterol. Much of the cholesterol came from eggs (Shekelle et al, 1991).

Cholesterol combines with lipoproteins as it is metabolised to form a high-density lipoprotein (H. D. L.) and low-density lipoprotein (L. D. L.). H. D. L. is “good” cholesterol as it is involved in transportation from the arteries and other tissues to the liver. L. D. L. is “bad” cholesterol because it contributes to the formation of plaque within the arteries. About two-thirds of the British population are at risk of CHD owing to high cholesterol levels.

Blood cholesterol levels are to a significant degree mediated by dietary intake of fats. In America 44% of calories are consumed as fat. The recommended level is 30%. Cholesterol levels are also affected by stress as stress causes cholesterol to not be metabolised by the liver. Other mediating factors are exercise levels and genetic factors.

Simone (1983) estimated that nutritional factors account for 60% of all cancer in women and 40% of all cancer in men in the USA.

Foods that are lacking in preservatives may result in high levels of bacteria and fungi being produced and spoiled food is a risk factor in stomach cancer. Food hygiene education and developments in food hygiene have produced a sharp decline in this disease.

Excessive use of salt has been linked to hypertension and to cardiovascular disease. High levels of fats and dietary cholesterol have been linked to atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD). A large scale study of Italian and American female breast cancer patients found that these patients do show increased fat intake in their diets; this was almost entirely due to their very high consumption of milk, high fat cheese and butter. Women who consumed half of their calories as fat had breast cancer rates that were three times higher than average. There was no difference between these cancer patients and healthy women in their consumption of carbohydrates and vegetable fats (Toniolo et al 1989). High intake of saturated fats is a risk factor for the severity of breast cancer in older women but not younger women (Verrault et al 1988). Both high and low levels of polyunsaturated facts were directly related to the severity of breast cancer of women.

Alcohol has been implicated in cancers of the tongue, oesophagus, liver and pancreas. In Norway frequent drinkers were five times more likely to suffer pancreatic cancer prepared with nondrinkers (Heuch et al, 1983). Drinking may also lead to cirrhosis of the liver.

Vitamins Aand C, and selenium, are thought to help reduce the risk of developing cancer. Deficiencies in vitamin A may lead to a deterioration in the stomachs protective lining. beta-carotene is a known protector against some types of cancer. Vitamin C also helps prevent the formation of nitrosamine carcinogens. Selenium is a trace element found in grain products and in meat from grain fed animals. In moderate amounts it may provide some protection against cancer.

High fibre diets protect men and women from cancer of the colon and the rectum. Fibre from fruits and vegetables offer more protection against colon cancer than that from cereals and other grains. Fruit consumption offers protection against lung cancer and we should be eating fruit 3 to 7 times per week (Fraser et al, 1991).

Obesity and eating disorders

Obesity and eating disorders

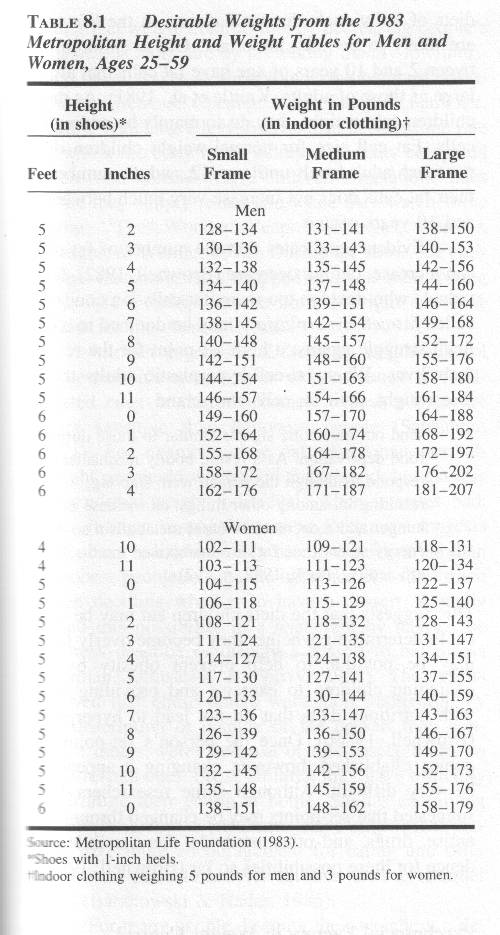

Obesity is defined in terms of the percentage and distribution of an individual's body fat. Techniques used to assess the body fat range from using computer tomography (e.g. ultrasound waves) to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Obesity may also be defined in terms of body mass index (B. M. I.) which is calculated by dividing a person's weight by their height squared using metric units (i.e. kilogrammes and metres squared). Stunkarda (1984) suggested that obesity should be categorised as either mild (20 to 40% overweight), moderate (41 to 100% overweight) or severe (more than 100% overweight). This would suggest that 24% of American men and 27% of American women are at least mildly obese (Kuczmarski, 1992).

Obesity is associated with physical health problems such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, joint trauma, cancer, hypertension and mortality. Obesity also is associated with psychological problems such as low self-esteem, and poor self image. Many people have false stereotypes and are misinformed about how others become obese. Such stereotypes probably were formulated in childhood (Lerner and Gellert, 1969).

There are three different types of theories that attempt to explain obesity; they are:

- Physiological theories suggesting that there are genetic elements.

- Metabolic rate theories proposing that obese people have a lower resting metabolic rate, burn up less calories when resting and therefore require less food. They also tend to have more fat cells which are genetically determined.

- Behavioural theories suggest that obese people tend to be less physically active and eat more food than required.

Eating disorders

The two main eating disorders are anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

Individuals are diagnosed as anorexic only if they weigh at least 15% less than their minimal normal weight and have stopped menstruating. In extreme cases, anorexics may weight less than 50% of their normal weight. Weight loss leads to a number of potentially dangerous side-effects, including emaciation (wasting of the body), susceptibility to infection and other symptoms of under nourishment. Females are 20 times more likely to develop anorexia than males. But horseracing Jockeys, who are usually male, are susceptible to anorexia. Anorexia particularly affects white, Western, middle to upper class, teenage women.

Another

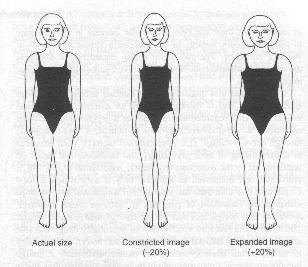

characteristic of anorexia nervosa is that of distortion of body image.

Anorexics think that they are too fat. This was investigated by Garfinkel and

Garner (1982). Participants used a device that could adjust pictures of

themselves and others up to 20 per cent above or below their actual body size. An anorexic was more likely to adjust the

picture of herself so that it was larger than the actual size. They did not do

the same for photographs of other people.

Another

characteristic of anorexia nervosa is that of distortion of body image.

Anorexics think that they are too fat. This was investigated by Garfinkel and

Garner (1982). Participants used a device that could adjust pictures of

themselves and others up to 20 per cent above or below their actual body size. An anorexic was more likely to adjust the

picture of herself so that it was larger than the actual size. They did not do

the same for photographs of other people.

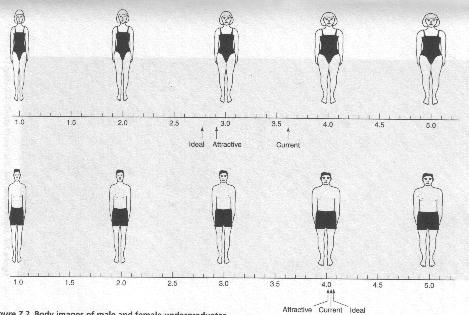

American undergraduates were shown figures of their own sex and asked to indicate the figure that looked most like their own shape, their ideal figure and the figure they found would be most attractive to the opposite sex. Men selected very similar figures for all three body shapes! Women chose ideal and attractive body shapes that were much thinner than the shape that was indicated as representing their current shape. Women tended to choose thinner body shapes for all three choices (ideal, attractive and current) compared to the men (Fallon and Rozin, 1985). The perfect figure has changed over the years. In the 1950s female sex symbols had much larger bodies compared with present-day female sex symbols.

The

hypothalamus is implicated in anorexia. The hypothalamus controls both eating

and hormonal functions (which may also explain irregularities in menstruation).

The

hypothalamus is implicated in anorexia. The hypothalamus controls both eating

and hormonal functions (which may also explain irregularities in menstruation).

Personality factors and family dynamics could also play a part in anorexia. The anorexic lacks self-confidence, needs approval, is conscientious, is a perfectionist and feels the pressure to succeed (Taylor, 1995). Parental psychopathology or alcoholism also plays a part as does being in an extremely close or interdependent family with poor skills for communicating emotion or dealing with conflict (Rakoff, 1983). The mother daughter relationship has been implicated. Mothers of anorexic daughters tend to be dissatisfied with their daughter's appearance and tend to be vulnerable to eating disorders themselves (Pike and Rodin, 1991). Genetics could explain this result as De Castro (2001) has found that identical twins have similar eating patterns compared with fraternal twins

Birch (2000) found that American 5 to 9 year olds whose parents stopped them from eating foods they condemned as fattening were at much greater risk of suffering weight and eating problems.

They lost the ability to regulate their own food intake and, were unable to understand cues from their bodies telling them whether they were hungry or not, binged on the restricted food whenever their parents were not around to stop them.

According to the researchers, it was the mothers who were most concerned about their own weight and who dieted most often who were most likely to risk their daughters' health and self-image by attempting to restrict their diet.

'Essentially, mothers who used more restriction had daughters who, in the absence of hunger, ate more snack foods when they were available. This indicated a heightened response to the presence of palatable food and a consequent reduction in the ability to regulate energy intake in response to hunger and satiety cues.' Revealingly, girls were far more likely to demonstrate this effect than boys.

The phenomenon, according to the study, appears to be connected to affluence. While many middle-class mothers were obsessed with keeping themselves and their daughters thin, low-income parents were more concerned with feeding their children enough and so were far less likely to restrict their diet.

Half of the 200 five-year-olds interviewed gave worryingly informed responses to questions about dieting and weight loss. Asked why people dieted, some responded that it was to get thin so they could 'get more dates'.

Abridged from The Observer 3rd Sept 2000

In treating anorexia the patients weight is brought back up to a safe level in a residential setting using behavioural techniques based on operant conditioning. Success in the residential setting may not translate to the home environment and therefore family therapy may be necessary to help families learn more positive methods of communicating emotion and conflict.

Bulimia

Bulimia is characterised by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by attempts to purge the excess eating by vomiting or using laxatives. The binges occur at least once a day usually in the evening and when alone. Vomiting and the use of laxatives disrupts the balance of the electrolyte potassium resulting in dehydration, cardiac arrhythmias and urinary infections.

This disorder mainly affects young women and is more common than anorexia affecting five to ten% of American women. Bulimia is not confined to middle or upper-class females and transcends racial, ethnic and socioeconomic boundaries. Like anorexia explanations encompass biological, personality and social factors. Bulimics often suffer from other disorders such as alcohol or drug abuse, impulsivity and kleptomania. It may be triggered by life events such as feeling guilty or feeling depressed. There is a stronger link between depression and bulimia compared with depression and anorexia. The depression seems to be linked to a deficit in the neurotransmitter substance serotonin. Bulimics may report lacking self-confidence and use food to fulfil their feelings of longing and emptiness. The binge eating and vomiting is justified in terms of needing to have a high calorie intake of food and a desire to stay slim.

Treatment involves medication and cognitive behavioural therapy. Antidepressants drugs are used in combination with psychotherapy. Treatment for bulimia tends to be more successful because bulimics recognise that they have a problem whereas anorexics don't.

HEALTH AND POVERTY

A British Longitudinal

Study, based on more than 12,000 participants has found that there is a 15 year

gap in quality of health between manual workers and professional workers. A third of men in manual jobs aged 50-59 had

a chronic illness, whereas only a quarter of professional men aged between 60

and 74 reported a chronic illness. (Times 5-12-03)

It is important to point out

that the most damaging lifestyles for

our health are those associated with low incomes. Throughout the Western world,

the most consistent predictor of illness and early death is income. People who

are unemployed, homeless, or on low incomes have higher rates of all the major

causes of premature death (Fitzpatrick and Dollamore, 1999; Carroll, Davey

Smith and Bennett, 1994). The reasons for this are not clear although there are

two main lines of argument. First, it is possible that people with low incomes

engage in risky behaviours more frequently, so they might smoke more cigarettes

and drink more alcohol. This argument probably owes more to negative

stereotypes of working-class people than it does to any systematic research.

The second line of argument

is that poor people are exposed to greater health risks in the environment in

the form of hazardous jobs and poor living accommodation. Also, people on low

incomes will probably buy cheaper foods which have a higher content of fat

(regarded as a risk factor for coronary heart disease). All this means that

psychological interventions on behaviour can only have a limited effect, since

it is economic circumstances that most affect the health of the nation.

The effects of poverty are

long lasting and far-reaching. A remarkable study by Dorling et al. (2000) compared late 20th century

death rates in London with modern patterns of poverty, and also with patterns

of poverty from the late 19th century. The researchers used information from

Charles Booth’s survey of inner London carried out in 1896, and matched it to

modern local government records. When they looked at the recent mortality (death) rates from diseases

that are commonly associated with poverty (such as stomach cancer, stroke and

lung cancer), they found that the measures of deprivation from 1896 were even

more strongly related to them than the deprivation measures from the 1990s.

They concluded that patterns of disease must have their roots in the past. It

is remarkable, but true, that geographical patterns of social deprivation and

disease are so strong that a century of change in inner London has not disrupted

them.

Another study by Dorling et al. (2001) plotted the mortality

ratio (rate of deaths compared to the national average) against voting patterns

in the 1997 general election. They divided the constituencies into ten

categories, ranging from those who had the highest Labour vote to those who had

the lowest. The analysis found that the constituencies with the highest Labour

vote (72 per cent on average) had the highest mortality ratio (127), and that

this ratio decreased in line with the proportion of people voting Labour, down

to the lower Labour vote (22 per cent on average) where there was a much lower

mortality ratio (84). This means that early death, and presumably poor health,

was more common in areas that chose to vote Labour. If we take Labour voting as

still being influenced by class and social status then this study gives us

another measure of the effects of wealth on health.

The influence of poverty

shows up in a number of ways. Glaucoma is a damaging eye disease that can cause

blindness if untreated. A study by Fraser et

al. (2001) looked at the differences between people who sought medical help

early (early presenters) and those who sought help for the first time when the

disease was already quite advanced (late presenters). The late presenters were

more likely to be in lower occupational classes, more likely to have left

full-time education at age 14 or younger, more likely to be tenants than owner

occupiers, and less likely to have access to a car. It showed that a persons personal

circumstances and the area they lived in had an effect on their decision to

seek help with their vision. It also appeared that the disease developed more

quickly in people with low incomes.

One uncomfortable

explanation of the differences in mortality rates for rich and poor might be

that the poor receive worse treatment from the NHS. Affluent women have a

higher incidence of breast cancer than women who are socially deprived, but

they have a better chance of survival. A study to investigate the care of the

breast cancer patients from the most and least well-off areas in Glasgow was

carried out by Macleod et al. (2000).

They looked at records from hospital and general practice to evaluate the

treatment that was given, the delay between consultation and treatment, and the

type and frequency of follow-up care. The data showed that women from the

affluent areas did not receive better care from the NHS. The women from the

deprived areas received similar treatment, were admitted to hospital more often

for other conditions than the cancer, and had more consultations after the

treatment than the women from the affluent areas. Perhaps the reasons for the

worse survival rate of women from deprived areas are not related to the quality

of care, but to the number and severity of other

diseases that they have alongside the cancer.

THE TYPE A BEHAVIOUR PATTERN

Do some lifestyles make

people more vulnerable to disease? Are we justified, for example, in

associating high stress behaviour with certain health problems such as heart

disease? Friedman and Rosenman (1959) investigated this and created a

description of behaviour patterns that has generated a large amount of research

and also become part of the general discussions on health in popular magazines.

Before we look at the work

of Friedman and Rosenman, it is worth making a psychological distinction

between behaviour patterns and personality. Textbooks and articles often refer

to the Type A personality, though, at

least in the original paper, the authors describe it as a behaviour pattern rather than a personality

type. The difference between these two is that a personality type is what you are, whereas a behaviour pattern is

what you do. The importance of this

distinction comes in our analysis of why we behave in a particular way (‘I was

made this way’ or ‘I learnt to be this way’), and what can be done about it. It

is easier to change a person’s pattern of learnt behaviour than it is to change

their nature.

Friedman and Rosenman

devised a description of Pattern A behaviour

that they expected to be associated with high levels of blood cholesterol

and hence coronary heart disease. This description was based on their previous

research and their clinical experience with patients. A summary of Pattern A

behaviour is given below:

(1) an intense, sustained drive

to achieve personal (and often poorly

defined) goals

(2) a profound tendency and

eagerness to compete in all

situations

(3) a persistent desire for recognition and advancement

(4) continuous involvement in

several activities at the same time that are constantly subject to deadlines

(5) an habitual tendency to rush to finish activities

(6) extraordinary mental and

physical alertness.

Pattern B behaviour, on the other

hand, is the opposite of Pattern A, characterised by the relative absence of

drive, ambition, urgency, desire to compete, or involvement in deadlines.

Research into type A behaviour

The classic study of Type A

and Type B behaviour patterns was a twelve-year longitudinal study of over

3,500 healthy middle-aged men reported by Friedman and Rosenman in 1974. They

found that, compared to people with the Type B behaviour pattern, people with

the Type A behaviour pattern were twice as likely to develop coronary heart

disease. Other researchers found that differences in the kinds of Type A

behaviour correlated with different kinds of heart disease: angina sufferers

tended to be impatient and intolerant with others, while those with heart

failure tended to be hurried and rushed, inflicting the pressures on

themselves.

A study by Ragland and Brand

(1988) illustrates how complex the relationship is between behaviour and

coronary heart disease. In their original study they found that measures of

Type A behaviour were useful in predicting the development of coronary heart

disease. However, in the follow-up study conducted 22 years later, the initial

behaviour pattern of the men was compared with their subsequent mortality

rates. Ragland and Brand found that among the 231 men who survived the first

coronary event for 24 hours or more, those who had initially displayed a Type A

behaviour pattern died at a much lower rate than the men who displayed a Type B

behaviour pattern (19.1 versus 31.7 per 1000 person-years). This finding was

rather unexpected and seems to contradict the general view about Type A

behaviour. One explanation is that people who display the Type A behaviour

pattern may respond differently to a heart attack than people who display the

Type B behaviour pattern. Alternatively, Type A behaviour patterns may cease to

be a risk factor after such an event. People may take the warning and change

their lifestyle.

Recent reviews of Type A behaviour suggest that it is not a useful measure

for predicting whether someone will have a heart attack or not. Myrtek (2001),

for example, looked at a wide range of studies on this issue and concluded that

measures of Type A and of hostility were so weakly associated with coronary

heart disease as to make them no use for prevention or prediction. The lasting

appeal of the Type A behaviour pattern is its simplicity and plausibility.

Unfortunately, health is rarely that simple and the interaction of stress with

physiological, psychological, social and cultural factors cannot be reduced to

two simple behaviour patterns.

Recent reviews of Type A behaviour suggest that it is not a useful measure

for predicting whether someone will have a heart attack or not. Myrtek (2001),

for example, looked at a wide range of studies on this issue and concluded that

measures of Type A and of hostility were so weakly associated with coronary

heart disease as to make them no use for prevention or prediction. The lasting

appeal of the Type A behaviour pattern is its simplicity and plausibility.

Unfortunately, health is rarely that simple and the interaction of stress with

physiological, psychological, social and cultural factors cannot be reduced to

two simple behaviour patterns.

RELIGIOSITY AND HEALTH

In 1921 Lewis Terman started

the Terman Life-Cycle Study looking at the lives of over 1500 people. The

sample was recruited from schools in California after the teachers identified

children who were gifted and had an lQ of 135 and above. The average year of

birth was 1910 so their age at the start of the study was 11 years. It was not

a very diverse sample, as they were mostly selected from white middle-class families,

but this apparent weakness is a strength if we want to look at the effect of

selected variables that do not include ethnicity and class. Data was collected

over the years and in 1950 (when the participants were aged about 40) they were

asked about their religiosity on a

four-point scale (not at all: little: moderate: strong). Forty years later the

researchers were able to compare this data against the mortality of the sample.

To cut to the chase, once the researchers had accounted for all the other

variables they were able to say that people who were more religious lived

longer (Clark et al. 1999).

Can having a pet lower your blood pressure? Karen Allen (State University

of New York, USA) surveyed the evidence.

Allen recalled studies dating from the 1980's that found pet ownership to

be a predictor of 1-yr survival after heart-attack; that pet-owning AIDS

sufferers suffer less from depression than non-owners; and that people with

pets have lower lipid levels (fats linked with risk of heart disease). A

more recent study by the author sought to remove the possible confound that

good health might lead people to become pet owners. Allen recruited a

sample of pet-free, stress-suffering stock-brokers with high blood pressure

and randomly allocated half of them to become an adopter of a cat or dog.

When they were put in a stress-inducing situation, the blood pressure of

the pet adopters rose by less than half that of the other, still pet-free

stock-brokers.

It sounds promising but Allen warned that "most researchers in this area

are pet enthusiasts" and that "researchers still do not know the

physiological consequences (to pet owners) when their pets die". Still, if

the research can be believed, it brings a whole new meaning to the

expression "a pet is for life, not just for Christmas".

Allen, K. (2003). Are pets a healthy pleasure? The influence of pets on

blood pressure. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 236-239.

Journal weblink: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/cd/

IS LAUGHTER THE BEST MEDICINE?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"A merry heart doeth good like a medicine", or so it says in the

Bible.

Gregory Boyle and Jeanne Joss-Reid, from the Universities of Bond and

Queensland in Australia, have investigated the link between humour and

health in 504 participants who completed comprehensive health and sense of

humour questionnaires.

For 300 healthy, non-student participants (a 'community group'), sense of

humour was modestly related to 3 of the 8 health factors investigated,

namely role limitations due to physical health, fatigue and emotional

wellness. This was so after controlling for a raft of variables including

exercise and marital status. Moreover, those community group members who

scored higher on humour also reported better health.

For 101 healthy students ('student group'), sense of humour was modestly

related to one health factor, namely emotional wellness. The students who

scored higher on humour also scored higher on emotional wellness.

Finally, for 103 unwell, non-student participants (the 'medical group'),

sense of humour was modestly related to just one health factor, namely

pain. In an opposite trend to the other groups, the unwell participants

with the higher humour scores also had the lower health scores.

The message, it seems, is clear. The relationship between health and humour

varies between those who have, and those who do not have a medical

condition. People who are unwell may turn to humour as a coping strategy,

but this doesn't mean that having a good sense of humour is associated with

having good health. Finally, doubt was cast on the generalisability of a

student sample.

Boyle, G.J. & Joss-Reid, J.M. (2004). Relationship of humour to health: a

psychometric investigation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 9, 51-66.

Journal weblink: http://www.bps.org.uk/publications/jHH_1.cfm

|

|

Cancer

rise 'led by changes in lifestyle'