Measuring pain

Summary

Karoly (1985) - we should focus on all of the factors that contribute to pain

1. Sensory - intensity, duration, threshold, tolerance, location, etc

2. Neurophysiological - brainwave activity, heart rate, etc

3. Emotional and motivational - anxiety, anger, depression, resentment, etc

4. Behavioural - avoidance of exercise, pain complaints, etc

5. Impact on lifestyle - marital distress, changes in sexual behaviour

6. Information processing - problem solving skills, coping styles, health beliefs

Techniques used to collect data.

1. interviews - advantage - it can cover Karoly's 6 points

2. behavioural observations

3. psychometric measures

4. medical records

5.

physiological measures

Physiological measures of pain

Muscle tension is associated with painful conditions such as headaches

and lower backache, and it can

be measured using an electromyograph (EMG). This apparatus

measures electrical activity in the muscles, which is a sign of how tense they

are. Some link has been established between headaches and EMG patterns, but EMG

recordings do not generally correlate with pain perception (Chapman et al 1985) and EMG measurements

have not been shown to be a useful way of measuring pain.

Another approach has been to relate pain to autonomic arousal. By taking measures of pulse rate, skin

conductance and skin temperature, it may be possible

to measure the physiological arousal caused by experiencing pain. Finally, since pain is

perceived within the brain, it may he possible to measure

brain activity, using an electroencephalograph

(EEG), in order to determine the extent to which an individual is

experiencing pain. It has been shown that subjective reports of pain do

correlate with electrical changes that show up as peaks in EEG recordings.

Moreover, when analgesics are given, both pain report and waveform amplitude on

the EEG are decreased (Chapman et al, 1985).

Evaluation

The advantage of the physiological measures of pain described above is

that they are objective (that is, not subject to bias by the person whose pain

is being measured, or by the person measuring the pain). On the other hand,

they involve the use of expensive machinery and trained personnel. Their main

disadvantage, however, is that they are not valid (that is, they do not measure

what they say they are measuring). For example, autonomic arousal can occur in

the absence of pain — being

wired up to a machine may be stressful and can cause a person’s heart rate to

increase. If someone is very anxious about the process of having his or her

pain assessed, or else is worried about the meaning of the pain, this will

cause physiological changes not necessarily related to the intensity of the

pain being experienced. Autonomic responses can be affected by many other

factors such as diet, alcohol consumption and infection. E.g. infection present

can get increased pulse rate. Better used as a signal for the presence of pain

rather than as a direct indices of pain.

Observations of pain

behaviours

People tend to behave in

certain ways when they are in pain; observing such behaviour could provide a

means of assessing pain.

Turk, Wack and Kerns (1985) have provided a classification of

observable pain behaviours.

• Facial /audible expression of distress: grimacing and teeth

clenching; moaning and sighing.

• Distorted ambulation or posture: limping or walking with a

stoop; moving slowly or carefully to protect an injury; supporting, rubbing or

holding a painful spot; frequently shifting position.

• Negative affect: feeling irritable; asking

for help in walking, or to be excused from activities; asking questions like

‘Why did this happen to me?’

• Avoidance of activity: lying down

frequently; avoiding physical activity; using a prosthetic device.

One way to assess pain behaviours is to observe them in a clinical

setting (although pain is also assessed in a natural setting as the patient

goes about his or her everyday activities). Keefe and Williams (1992) have

identified five elements that need to be considered when preparing to assess

any form of behaviour through this type of observation.

• A rationale for observation: it is

important for clinicians to know why they are observing pain behaviours. One

reason is to identify ‘problem’ behaviours that the patient may be reluctant to

report, such as pain when swallowing, so that treatment can be given. Another

is to monitor the progress of a course of treatment.

• A method for sampling pain behaviour techniques for sampling and

recording behaviour include continuous observation, measuring duration (how

long the patient takes to complete a task), frequency counts (the number of

times a target behaviour occurs) and time sampling (for example, observing the

patient for five minutes every hour).

• Definitions of the behaviour: observers need to be

completely clear as to what behaviours they are looking for.

• Observer training: in most clinical situations,

there will be different observers at different times and it is

important that they are consistent.

• Reliability and validity: the most useful measure of

consistency in observation methods is inter-rater reliability, but test-retest

reliability can also be useful. Three types of validity that could be assessed

are: concurrent validity (are the results of the observation consistent with

another measure of the same behaviour?), construct validity (are the

behaviours being recorded really signs of pain?) and discriminant validity (do

the observation records discriminate between patients with and without pain?).

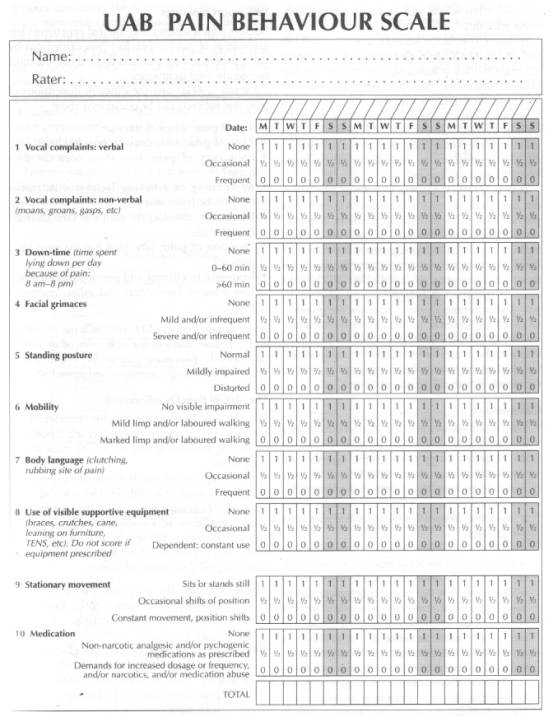

A commonly used example of

an observation tool for, assessing pain behaviour is the UAB Pain Behaviour Scale designed by Richards et al (1982). This scale consists of ten target behaviours and observers

have to rate how frequently each occurs.  The UAB is easy to use and

quick to score; it has scored well on inter-rater and test-retest

reliability.

The UAB is easy to use and

quick to score; it has scored well on inter-rater and test-retest

reliability.

However, correlation between scores on the UAB

and on the McGill Pain Questionnaire is low indicating that the relationship

between observable pain behaviour and the self-reports of the subjective

experience of pain is not a close one. Turk et al (1983) describe techniques

that someone living with the patient (the observer) can use to provide a

record of their pain behaviour. These include asking the observer to keep a

pain diary, which includes a record of when the patient is in pain and for how

long, how the observer recognized the pain, what the observer thought and felt

at the time, and how the observer attempted to help the patient alleviate the

pain. Other techniques are to interview the observer, or to ask the observer to

complete a questionnaire containing questions about how much the pain interferes

with the patient’s normal activities and social life, the effect of the pain on

family relationships and on the moods of both patient and observer.

Commentary

• Behavioural assessment is less objective

than taking physiological measurements, because it relies on the observer’s interpretation

of the patient’s pain behaviours (although, in practice, this can be partly

dealt with by using clearly defined checklists of behaviour and carrying out

inter-rater reliability — that

is, using two independent observers

and comparing their findings).

• An individual may be displaying a great deal

of pain behaviour, not because that individual is in severe pain but because

he or she is receiving social reinforcement for the pain behaviour (for

example, attention, sympathy and time off work). A by Gil et al (1988) provides an example of this: the children whose pain

behaviour (scratching their eczema) was rewarded with attention exhibited more

of this behaviour.

Self-report measures

Because pain is a subjective, internal experience, the assessment of

pain is therefore best carried out by using patient self-reports, and this is

by far the most frequently used technique.

Carroll (1993a) lists the different dimensions

of pain that sufferers can be questioned about:

• Site of pain: where

is the pain?

• Type of

pain: what does the pain feel like?

• Frequency of

pain: how often does the pain occur?

• Aggravating

or relieving factors: what makes the pain better or worse?

• Disability: how does the pain affect the patient’s everyday life?

• Duration

of pain: how long has the pain been present?

• Response to

current and previous treatments: how effective have

drugs and other treatments been?

An important item to add to this list is the emotional and cognitive effect

of the pain—in other words, how does the pain make patients feel and how does

it affect their thought processes and attitudes?

Two types of

self-rating scales

1. Visual

analogue

Patients mark a continuum of

severity from "No Pain" to "Very Severe Pain"

Patients mark a continuum of

severity from "No Pain" to "Very Severe Pain"

Simple and Quick to

use and can be filled out repeatedly

Can track the pain

experience as it changes - this could reveal patterns such as situations or

times of the day when the pain is better or worse

This method has

adequate reliability, however limits pain to a single dimension. Downie and colleagues evaluated

the degree of agreement between various scales in patients with rheumatic

diseases and found a high correlation among the different types of scales. The

scales are simple to understand and do not demand a high degree of literacy or

sophistication on the part of the patient, unlike other pain measurement tools,

such as the semantic differential scales described below. The Visual Analogue

Scale is simple and quick to administer, and may be used before, during, and

following treatment to evaluate changes in the patient's perception of pain

relative to treatment. The scales may also be completed throughout the course

of a day to assess change in pain intensity relative to activity or time of day.

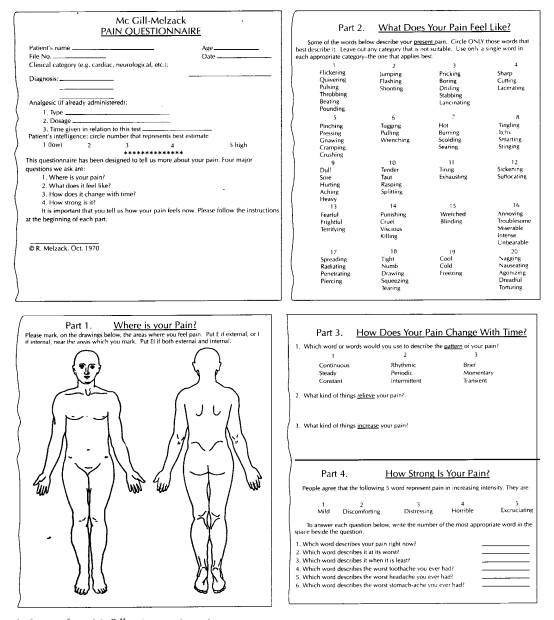

2. McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

The McGill Pain Questionnaire, developed by Melzack

(1975), was the first proper self-report pain-measuring instrument and is still

the most widely used today.

An attempt to find words to describe

experiences of pain was made in a study by Melzack and Torgerson (1971) in

which they asked doctors and university graduates to classify 102 adjectives

into groups describing different aspects of pain. As a result of this exercise,

they identified three major psychological dimensions of pain:

• sensory: what the pain feels like physically —where it is located, how

intense it is, its duration and its

quality (for example, ‘burning’, ‘throbbing’)

• affective: what the pain feels like emotionally —whether it is frightening, worrying

and so on

• evaluative: what the subjective overall intensity of the pain experience is (for

example, ‘unbearable’, ‘distressing’).

Each of the three main classes was divided into a number of sub-classes (sixteen

in total). For example, the affective class was sub-divided into tension

(including the adjectives ‘tiring’, ‘exhausting’), autonomic (including

‘sickening’, ‘suffocating’) and fear (including ‘fearful’, ‘frightful’,

‘terrifying’).

Melzack and Torgerson (1971) then asked a sample

of doctors, patients and students to rate the words in each sub-class for

intensity. The first 20 questions on the McGill Pain Questionnaire consist of

adjectives set out within their sub-classes, in order of intensity. Questions 1

to 10 are sensory, 11 to 15 affective, 16 is evaluative and 17 to 20 are miscellaneous.

Patients are asked to tick the word

in each subclass that best describes their pain. Based on this, a pain rating index (PRJ) is calculated:

each sub-class is effectively a verbal rating scale and is scored accordingly

(that is, 1 for the adjective describing

least intensity, 2 for the next one and so on). Scores are given for the

different classes (sensory, affective, evaluative and miscellaneous), and also

a total score for all the sub-classes. In addition, patients are asked to

indicate the location of the pain on a body chart (using the codes E for pain

on the surface of the body, I for internal pain and El for both external and

internal), and to indicate present pain intensity (PPJ) on a 6-point verbal

rating scale. Finally, patients complete a set of three verbal rating scales

describing the pattern of the pain.

Criticism of this questionnaire centres on the need

to have extensive understanding of the English language eg discriminate between

words such as "Smarting" and "Stinging"

Semantic differential scales, such as the McGill, are difficult and time

consuming to complete and demand a sophisticated literacy level, a sufficient

attention span, and a normal cognitive state. They therefore are less

convenient to use in the clinical environment, but have value when a more

detailed analysis of a patient's perception of pain is needed, as in a pain

clinic or clinical research setting.

The issue of reliability has been addressed in numerous reports, particularly as it concerns the VAS and the McGill Pain Questionnaire. These reports do not lead to a consensus on reliability of these measurements. They suggest that reliability varies based on the patient groups that were examined for pain. Reliability therefore becomes an issue of "reliable in whose hands?" Reliability of many of the pain measurement methods have not extended in any realistic way beyond the reliability found by the original authors of the pain measurement methods.

A lack of clear reliability information should not prevent the clinician from using these methods, but it should alert the clinician to the possibility that a particular method may not be reliable with a particular patient or a group of patients. The clinician also should ensure that those who use the measurements for their own purposes will be aware of the limitations of these measurements.37

A difficult aspect of reliability is that the patient may have developed a different understanding of the pain problem and may give a different response from one examination to the next. It is equally important for the examiner to ask himself or herself whether the interpretation of the patient's responses differs from one examination to the next. Both factors affect the reliability of the information being gathered.37

Perhaps it is worthwhile to reexamine the concepts of subjective and objective measurements. Sometimes the terms "objective" and "subjective" are concerned not with the reliability of a measurement, but with the nature of what is being measured. It could be argued that pain is a subjective phenomenon, but if it is measured reliably, the quality of the measurement would be objective.

Acknowledgements

Philippe Harari and Karen Legge (2001), Psychology and Health, Heinemann, 0-435-80659-9. Highly recommended, easy to read, affordable text; a must have for every student.

LINKS

Continue with Controlling Pain

Return to Nature and Symptoms of Pain